This page contains two lists (1) neuroscience-based commentaries & reviews of the literature, and, (2) neurological studies assessing the brain structure and functioning of Internet porn users and sex/porn addicts (Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder).

This page contains two lists (1) neuroscience-based commentaries & reviews of the literature, and, (2) neurological studies assessing the brain structure and functioning of Internet porn users and sex/porn addicts (Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder).

Reviews of the literature & commentaries:

1) Neuroscience of Internet Pornography Addiction: A Review and Update (Love et al., 2015). A thorough review of the neuroscience literature related to Internet addiction sub-types, with special focus on internet porn addiction. The review also critiques two headline-grabbing EEG studies by teams headed by Nicole Prause (who claims the findings cast doubt on porn addiction). Excerpts:

Many recognize that several behaviors potentially affecting the reward circuitry in human brains lead to a loss of control and other symptoms of addiction in at least some individuals. Regarding Internet addiction, neuroscientific research supports the assumption that underlying neural processes are similar to substance addiction… Within this review, we give a summary of the concepts proposed underlying addiction and give an overview about neuroscientific studies on Internet addiction and Internet gaming disorder. Moreover, we reviewed available neuroscientific literature on Internet pornography addiction and connect the results to the addiction model. The review leads to the conclusion that Internet pornography addiction fits into the addiction framework and shares similar basic mechanisms with substance addiction.

3.4. Neuroadaptations Related to Internet Pornography-Induced Sexual Difficulties: We hypothesize that pornography-induced sexual difficulties involve both hyperactivity and hypoactivity in the brain’s motivational system [72, 129] and neural correlates of each, or both, have been identified in recent studies on Internet pornography users [31, 48, 52, 53, 54, 86, 113, 114, 115, 120, 121, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134].

2) Sex Addiction as a Disease: Evidence for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Response to Critics (Phillips et al., 2015), which provides a chart that takes on specific criticisms of porn/sex addiction, offering citations that counter them. Excerpts:

As seen throughout this article, the common criticisms of sex as a legitimate addiction do not hold up when compared to the movement within the clinical and scientific communities over the past few decades. There is ample scientific evidence and support for sex as well as other behaviors to be accepted as addiction. This support is coming from multiple fields of practice and offers incredible hope to truly embrace change as we better understand the problem. Decades of research and developments in the field of addiction medicine and neuroscience reveal the underlying brain mechanisms involved in addiction. Scientists have identified common pathways affected by addictive behavior as well as differences between the brains of addicted and non-addicted individuals, revealing common elements of addiction, regardless of the substance or behavior. However, there remains a gap between the scientific advances and the understanding by the general public, public policy, and treatment advances.

3) Cybersex Addiction (Brand & Laier, 2015). Excerpts:

Many individuals use cybersex applications, particularly Internet pornography. Some individuals experience a loss of control over their cybersex use and report that they cannot regulate their cybersex use even if they experienced negative consequences. In recent articles, cybersex addiction is considered a specific type of Internet addiction. Some current studies investigated parallels between cybersex addiction and other behavioral addictions, such as Internet Gaming Disorder. Cue-reactivity and craving are considered to play a major role in cybersex addiction. Also, neurocognitive mechanisms of development and maintenance of cybersex addiction primarily involve impairments in decision making and executive functions. Neuroimaging studies support the assumption of meaningful commonalities between cybersex addiction and other behavioral addictions as well as substance dependency.

4) Neurobiology of Compulsive Sexual Behavior: Emerging Science (Kraus et al., 2016). Excerpts:

Although not included in DSM-5, compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) can be diagnosed in ICD-10 as an impulse control disorder. However, debate exists about CSB’s classification. Additional research is needed to understand how neurobiological features relate to clinically relevant measures like treatment outcomes for CSB. Classifying CSB as a ‘behavioral addiction’ would have significant implications for policy, prevention and treatment efforts….. Given some similarities between CSB and drug addictions, interventions effective for addictions may hold promise for CSB, thus providing insight into future research directions to investigate this possibility directly.

5) Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? (Kraus et nal., 2016). Excerpts:

With the release of DSM-5, gambling disorder was reclassified with substance use disorders. This change challenged beliefs that addiction occurred only by ingesting of mind-altering substances and has significant implications for policy, prevention and treatment strategies. Data suggest that excessive engagement in other behaviors (e.g. gaming, sex, compulsive shopping) may share clinical, genetic, neurobiological and phenomenological parallels with substance addictions.

Another area needing more research involves considering how technological changes may be influencing human sexual behaviors. Given that data suggest that sexual behaviors are facilitated through Internet and smartphone applications, additional research should consider how digital technologies relate to CSB (e.g. compulsive masturbation to Internet pornography or sex chatrooms) and engagement in risky sexual behaviors (e.g. condomless sex, multiple sexual partners on one occasion).

Overlapping features exist between CSB and substance use disorders. Common neurotransmitter systems may contribute to CSB and substance use disorders, and recent neuroimaging studies highlight similarities relating to craving and attentional biases. Similar pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments may be applicable to CSB and substance addictions.

6) Neurobiological Basis of Hypersexuality (Kuhn & Gallinat, 2016). Excerpts:

Behavioral addictions and in particular hypersexuality should remind us of the fact that addictive behavior actually relies on our natural survival system. Sex is an essential component in survival of species since it is the pathway for reproduction. Therefore it is extremely important that sex is considered pleasurable and has primal rewarding properties, and although it may turn into an addiction at which point sex may be pursued in a dangerous and counterproductive way, the neural basis for addiction might actually serve very important purposes in primal goal pursuit of individuals…. Taken together, the evidence seems to imply that alterations in the frontal lobe, amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus, septum, and brain regions that process reward play a prominent role in the emergence of hypersexuality. Genetic studies and neuropharmacological treatment approaches point at an involvement of the dopaminergic system.

7) Compulsive Sexual Behaviour as a Behavioural Addiction: The Impact of the Internet and Other Issues (Griffiths, 2016). Excerpts:

I have carried out empirical research into many different behavioural addictions (gambling, video-gaming, internet use, exercise, sex, work, etc.) and have argued that some types of problematic sexual behaviour can be classed as sex addiction, depending upon the definition of addiction used….

Whether problematic sexual behaviour is described as compulsive sexual behavior (CSB), sex addiction and/or hypersexual disorder, there are thousands of psychological therapists around the world who treat such disorders. Consequently, clinical evidence from those who help and treat such individuals should be given greater credence by the psychiatric community….

Arguably the most important development in the field of CSB and sex addiction is how the internet is changing and facilitating CSB. This was not mentioned until the concluding paragraph, yet research into online sex addiction (while comprising a small empirical base) has existed since the late 1990s, including sample sizes of up to almost 10 000 individuals. In fact, there have been recent reviews of empirical data concerning online sex addiction and treatment. These have outlined the many specific features of the internet that may facilitate and stimulate addictive tendencies in relation to sexual behaviour (accessibility, affordability, anonymity, convenience, escape, disinhibition, etc.).

8) Searching for Clarity in Muddy Water: Future Considerations for Classifying Compulsive Sexual Behavior as An Addiction (Kraus et al., 2016). Excerpts:

We recently considered evidence for classifying compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) as a non-substance (behavioral) addiction. Our review found that CSB shared clinical, neurobiological and phenomenological parallels with substance-use disorders….

Although the American Psychiatric Association rejected hypersexual disorder from DSM-5, a diagnosis of CSB (excessive sex drive) can be made using ICD-10. CSB is also being considered by ICD-11, although its ultimate inclusion is not certain. Future research should continue to build knowledge and strengthen a framework for better understanding CSB and translating this information into improved policy, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment efforts to minimize the negative impacts of CSB.

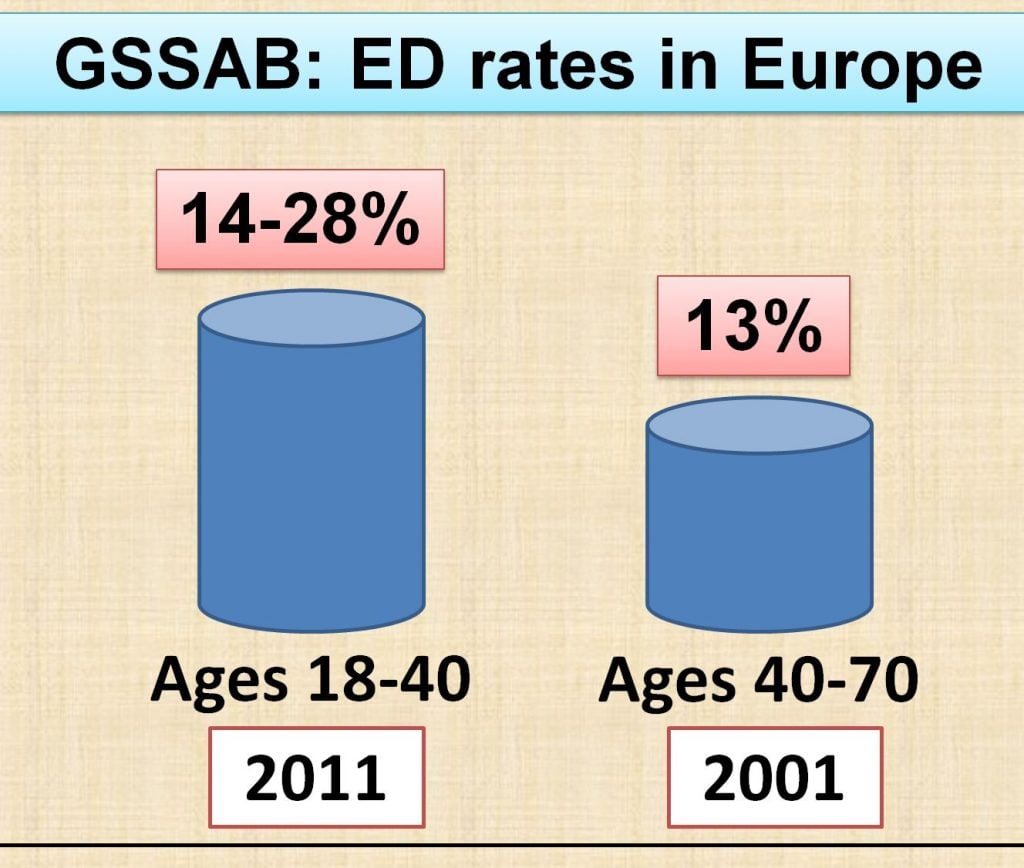

9) Is Internet Pornography Causing Sexual Dysfunctions? A Review With Clinical Reports (Park et al., 2016). An extensive review of the literature related to porn-induced sexual problems. Involving 7 US Navy doctors and Gary Wilson, the review provides the latest data revealing a tremendous rise in youthful sexual problems. It also reviews the neurological studies related to porn addiction and sexual conditioning via Internet porn. The doctors provide 3 clinical reports of men who developed porn-induced sexual dysfunctions. A second 2016 paper by Gary Wilson discusses the importance of studying the effects of porn by having subjects abstain from porn use: Eliminate Chronic Internet Pornography Use to Reveal Its Effects (2016). Excerpt:

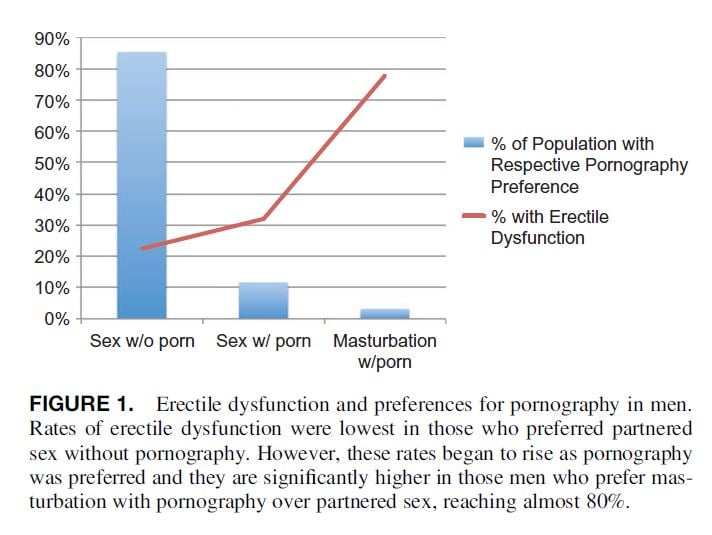

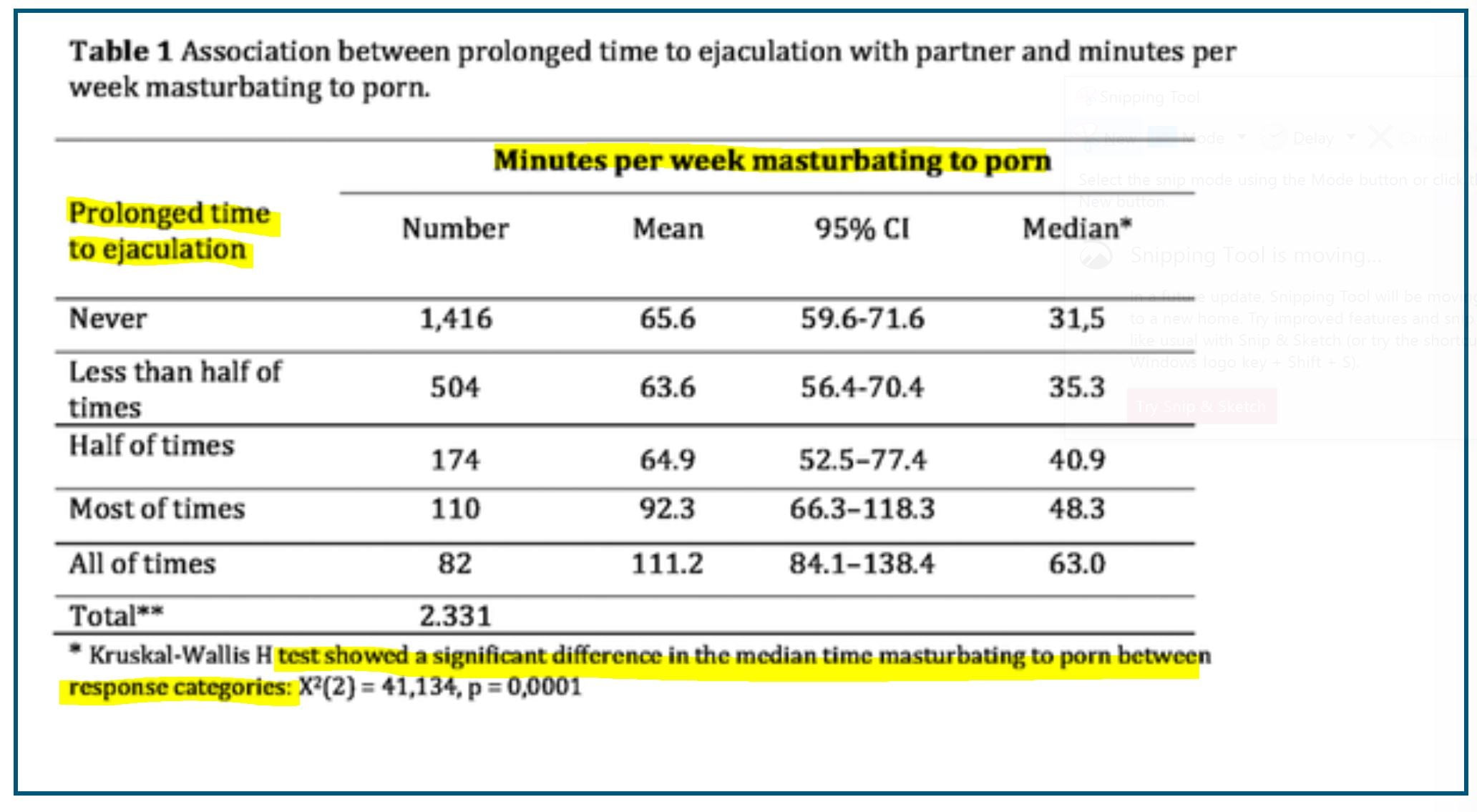

Traditional factors that once explained men’s sexual difficulties appear insufficient to account for the sharp rise in erectile dysfunction, delayed ejaculation, decreased sexual satisfaction, and diminished libido during partnered sex in men under 40. This review (1) considers data from multiple domains, e.g., clinical, biological (addiction/urology), psychological (sexual conditioning), sociological; and (2) presents a series of clinical reports, all with the aim of proposing a possible direction for future research of this phenomenon. Alterations to the brain’s motivational system are explored as a possible etiology underlying pornography-related sexual dysfunctions. This review also considers evidence that Internet pornography’s unique properties (limitless novelty, potential for easy escalation to more extreme material, video format, etc.) may be potent enough to condition sexual arousal to aspects of Internet pornography use that do not readily transition to real-life partners, such that sex with desired partners may not register as meeting expectations and arousal declines. Clinical reports suggest that terminating Internet pornography use is sometimes sufficient to reverse negative effects, underscoring the need for extensive investigation using methodologies that have subjects remove the variable of Internet pornography use.

10) Integrating Psychological and Neurobiological Considerations Regarding The Development and Maintenance of Specific Internet-Use Disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution model (Brand et al., 2016). A review of the mechanisms underlying the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders, including “Internet-pornography-viewing disorder”. The authors suggest that pornography addiction (and cybersex addiction) be classified as internet use disorders and placed with other behavioral addictions under substance-use disorders as addictive behaviors. Excerpts:

Although the DSM-5 focuses on Internet gaming, a meaningful number of authors indicate that treatment-seeking individuals may also use other Internet applications or sites addictively….

From the current state of research, we suggest to include Internet-use disorders in the upcoming ICD-11. It is important to note that beyond Internet-gaming disorder, other types of applications are also used problematically. One approach could involve the introduction of a general term of Internet-use disorder, which could then be specified considering the first-choice application that is used (for example Internet-gaming disorder, Internet-gambling disorder, Internet-pornography-use disorder, Internet-communication disorder, and Internet-shopping disorder).

11) The Neurobiology of Sexual Addiction: Chapter from Neurobiology of Addictions, Oxford Press (Hilton et al., 2016) – Excerpts:

We review the neurobiological basis for addiction, including natural or process addiction, and then discuss how this relates to our current understanding of sexuality as a natural reward that can become functionally “unmanageable” in an individual’s life….

It is clear that the current definition and understanding of addiction has changed based with the infusion of knowledge regarding how the brain learns and desires. Whereas sexual addiction was formerly defined based solely on behavioral criteria, it is now seen also through the lens of neuromodulation. Those who will not or cannot understand these concepts may continue to cling to a more neurologically naïve perspective, but those who are able to comprehend the behavior in the context of the biology, this new paradigm provides an integrative and functional definition of sexual addiction which informs both the scientist and the clinician.

12) Neuroscientific Approaches to Online Pornography Addiction (Stark & Klucken, 2017) – Excerpts:

The availability of pornographic material has substantially increased with the development of the Internet. As a result of this, men ask for treatment more often because their pornography consumption intensity is out of control; i.e., they are not able to stop or reduce their problematic behavior although they are faced with negative consequences…. In the last two decades, several studies with neuroscientific approaches, especially functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), were conducted to explore the neural correlates of watching pornography under experimental conditions and the neural correlates of excessive pornography use. Given previous results, excessive pornography consumption can be connected to already known neurobiological mechanisms underlying the development of substance-related addictions.

Finally, we summarized the studies, which investigated the correlates of excessive pornography consumption on a neural level. Despite a lack of longitudinal studies, it is plausible that the observed characteristics in men with sexual addiction are the results not the causes of excessive pornography consumption. Most of the studies report stronger cue reactivity in the reward circuit toward sexual material in excessive pornography users than in control subjects, which mirrors the findings of substance-related addictions. The results concerning a reduced prefrontal-striatal-connectivity in subjects with pornography addiction can be interpreted as a sign of an impaired cognitive control over the addictive behavior.

13) Is excessive sexual behaviour an addictive disorder? (Potenza et al., 2017) – Excerpts:

Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder (operationalised as hypersexual disorder) was considered for inclusion in DSM-5 but ultimately excluded, despite the generation of formal criteria and field trial testing. This exclusion has hindered prevention, research, and treatment efforts, and left clinicians without a formal diagnosis for compulsive sexual behaviour disorder.

Research into the neurobiology of compulsive sexual behaviour disorder has generated findings relating to attentional biases, incentive salience attributions, and brain-based cue reactivity that suggest substantial similarities with addictions. Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder is being proposed as an impulse-control disorder in ICD-11, consistent with a proposed view that craving, continued engagement despite adverse consequences, compulsive engagement, and diminished control represent core features of impulse-control disorders. This view might have been appropriate for some DSM-IV impulse-control disorders, specifically pathological gambling. However, these elements have long been considered central to addictions, and in the transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5, the category of Impulse Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified was restructured, with pathological gambling renamed and reclassified as an addictive disorder. At present, the ICD-11 beta draft site lists the impulse-control disorders, and includes compulsive sexual behaviour disorder, pyromania, kleptomania, and intermittent explosive disorder.

Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder seems to fit well with non-substance addictive disorders proposed for ICD-11, consistent with the narrower term of sex addiction currently proposed for compulsive sexual behaviour disorder on the ICD-11 draft website. We believe that classification of compulsive sexual behaviour disorder as an addictive disorder is consistent with recent data and might benefit clinicians, researchers, and individuals suffering from and personally affected by this disorder.

14) Neurobiology of Pornography Addiction – A clinical review (De Sousa & Lodha, 2017) – Excerpts:

The review first looks at the basic neurobiology of addiction with the basic reward circuit and structures involved generally in any addiction. The focus then shifts to pornography addiction and studies done on the neurobiology of the condition are reviewed. The role of dopamine in pornography addiction is reviewed along with the role of certain brain structures as seen on MRI studies. fMRI studies involving visual sexual stimuli have been used widely to study the neuroscience behind pornography usage and the findings from these studies are highlighted. The effect of pornography addiction on higher order cognitive functions and executive function is also stressed.

In total, 59 articles were identified which included reviews, mini reviews and original research papers on the issues of pornography usage, addiction and neurobiology. The research papers reviewed here were centered on those that elucidated a neurobiological basis for pornography addiction. We included studies that had decent sample size and sound methodology with appropriate statistical analysis. There were some studies with fewer participants, case series, case reports and qualitative studies that were also analyzed for this paper. Both the authors reviewed all the papers and the most relevant ones were chosen for this review. This was further supplemented with the personal clinical experience of both the authors who work regularly with patients where pornography addiction and viewing is a distressing symptom. The authors also have psychotherapeutic experience with these patients that have added value to the neurobiological understanding.

15) The Proof of the Pudding Is in the Tasting: Data Are Needed to Test Models and Hypotheses Related to Compulsive Sexual Behaviors (2018) – Excerpts:

As described elsewhere (Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016a), there is an increasing number of publications on CSB, reaching over 11,400 in 2015. Nonetheless, fundamental questions on the conceptualization of CSB remain unanswered (Potenza, Gola, Voon, Kor, & Kraus, 2017). It would be relevant to consider how the DSM and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) operate with respect to definition and classification processes. In doing so, we think it is relevant to focus on gambling disorder (also known as pathological gambling) and how it was considered in DSM-IV and DSM-5 (as well as in ICD-10 and the forthcoming ICD-11). In DSM-IV, pathological gambling was categorized as an “Impulse-Control Disorder Not Elsewhere Classified.” In DSM-5, it was reclassified as a “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorder.”…. A similar approach should be applied to CSB, which is currently being considered for inclusion as an impulse-control disorder in ICD-11 (Grant et al., 2014; Kraus et al., 2018)….

Among the domains that may suggest similarities between CSB and addictive disorders are neuroimaging studies, with several recent studies omitted by Walton et al. (2017). Initial studies often examined CSB with respect to models of addiction (reviewed in Gola, Wordecha, Marchewka, & Sescousse, 2016b; Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016b). A prominent model—the incentive salience theory (Robinson & Berridge, 1993)—states that in individuals with addictions, cues associated with substances of abuse may acquire strong incentive values and evoke craving. Such reactions may relate to activations of brain regions implicated in reward processing, including the ventral striatum. Tasks assessing cue reactivity and reward processing may be modified to investigate the specificity of cues (e.g., monetary versus erotic) to specific groups (Sescousse, Barbalat, Domenech, & Dreher, 2013), and we have recently applied this task to study a clinical sample (Gola et al., 2017). We found that individuals seeking treatment for problematic pornography use and masturbation, when compared to matched (by age, gender, income, religiosity, amount of sexual contacts with partners, sexual arousability) healthy control subjects, showed increased ventral striatal reactivity for cues of erotic rewards, but not for associated rewards and not for monetary cues and rewards. This pattern of brain reactivity is in line with the incentive salience theory and suggests that a key feature of CSB may involve cue reactivity or craving induced by initially neutral cues associated with sexual activity and sexual stimuli. Additional data suggest that other brain circuits and mechanisms may be involved in CSB, and these may include anterior cingulate, hippocampus and amygdala (Banca et al., 2016; Klucken, Wehrum-Osinsky, Schweckendiek, Kruse, & Stark, 2016; Voon et al., 2014). Among these, we have hypothesized that the extended amygdala circuit that relates to high reactivity for threats and anxiety may be particularly clinically relevant (Gola, Miyakoshi, & Sescousse, 2015; Gola & Potenza, 2016) based on observation that some CSB individuals present with high levels of anxiety (Gola et al., 2017) and CSB symptoms may be reduced together with pharmacological reduction in anxiety (Gola & Potenza, 2016)…

16) Promoting educational, classification, treatment, and policy initiatives Commentary on: Compulsive sexual behaviour disorder in the ICD-11 (Kraus et al., 2018) – The world’s most widely used medical diagnostic manual, The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), contains a new diagnosis suitable for porn addiction: “Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder.” Excerpts:

For many individuals who experience persistent patterns of difficulty or failures in controlling intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges that result in sexual behavior associated with marked distress or impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, it is very important to be able to name and identify their problem. It is also important that care providers (i.e., clinicians and counselors) from whom individuals may seek help are familiar with CSBs. During our studies involving over 3,000 subjects seeking treatment for CSB, we have frequently heard that individuals suffering from CSB encounter multiple barriers during their seeking of help or in contact with clinicians (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2016). Patients report that clinicians may avoid the topic, state that such problems do not exist, or suggest that one has a high sexual drive, and should accept it instead of treating (despite that for these individuals, the CSBs may feel ego-dystonic and lead to multiple negative consequences). We believe that well-defined criteria for CSB disorder will promote educational efforts including development of training programs on how to assess and treat individuals with symptoms of CSB disorder. We hope that such programs will become a part of clinical training for psychologists, psychiatrists, and other providers of mental health care services, as well as other care providers including primary care providers, such as generalist physicians.

Basic questions on how best to conceptualize CSB disorder and provide effective treatments should be addressed. The current proposal of classifying CSB disorder as an impulse-control disorder is controversial as alternate models have been proposed (Kor, Fogel, Reid, & Potenza, 2013). There are data suggesting that CSB shares many features with addictions (Kraus et al., 2016), including recent data indicating increased reactivity of reward-related brain regions in response to cues associated with erotic stimuli (Brand, Snagowski, Laier, & Maderwald, 2016; Gola, Wordecha, Marchewka, & Sescousse, 2016; Gola et al., 2017; Klucken, Wehrum-Osinsky, Schweckendiek, Kruse, & Stark, 2016; Voon et al., 2014). Furthermore, preliminary data suggest that naltrexone, a medication with indications for alcohol- and opioid-use disorders, may be helpful for treating CSBs (Kraus, Meshberg-Cohen, Martino, Quinones, & Potenza, 2015; Raymond, Grant, & Coleman, 2010). With respect to CSB disorder’s proposed classification as an impulse-control disorder, there are data suggesting that individuals seeking treatment for one form of CSB disorder, problematic pornography use, do not differ in terms of impulsivity from the general population. They are instead presented with increased anxiety (Gola, Miyakoshi, & Sescousse, 2015; Gola et al., 2017), and pharmacological treatment targeting anxiety symptoms may be helpful in reducing some CSB symptoms (Gola & Potenza, 2016). While it may not yet be possible to draw definitive conclusions regarding classification, more data seem to support classification as an addictive disorder when compared to an impulse-control disorder (Kraus et al., 2016), and more research is needed to examine relationships with other psychiatric conditions (Potenza et al., 2017).

17) Compulsive Sexual Behavior in Humans and Preclinical Models (2018) – Excerpts:

Compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) is widely regarded as a “behavioral addiction,” and is a major threat to quality of life and both physical and mental health. However, CSB has been slow to be recognized clinically as a diagnosable disorder. CSB is co-morbid with affective disorders as well as substance use disorders, and recent neuroimaging studies have demonstrated shared or overlapping neural pathologies disorders, especially in brain regions controlling motivational salience and inhibitory control. Clinical neuroimaging studies are reviewed that have identified structural and/or function changes in prefrontal cortex, amygdala, striatum, and thalamus in individuals suffering from CSB. A preclinical model to study the neural underpinnings of CSB in male rats is discussed consisting of a conditioned aversion procedure to examine seeking of sexual behavior despite known negative consequences.

Because CSB shares characteristics with other compulsive disorders, namely, drug addiction, comparisons of findings in CSB, and drug-addicted subjects, may be valuable to identify common neural pathologies mediating comorbidity of these disorders. Indeed, many studies have shown similar patterns of neural activity and connectivity within limbic structures that are involved in both CSB and chronic drug use [87–89].

In conclusion, this review summarized the behavioral and neuroimaging studies on human CSB and comorbidity with other disorders, including substance abuse. Together, these studies indicate that CSB is associated with functional alterations in dorsal anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex, amygdala, striatum, and thalamus, in addition to decreased connectivity between amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Moreover, a preclinical model for CSB in male rats was described, including new evidence of neural alterations in mPFC and OFC that are correlated with loss of inhibitory control of sexual behavior. This preclinical model offers a unique opportunity to test key hypotheses to identify predispositions and underlying causes of CSB and comorbidity with other disorders.

18) Sexual Dysfunctions in the Internet Era (2018) – Excerpt:

Low sexual desire, reduced satisfaction in sexual intercourse, and erectile dysfunction (ED) are increasingly common in young population. In an Italian study from 2013, up to 25% of subjects suffering from ED were under the age of 40 [1], and in a similar study published in 2014, more than half of Canadian sexually experienced men between the age of 16 and 21 suffered from some kind of sexual disorder [2]. At the same time, prevalence of unhealthy lifestyles associated with organic ED has not changed significantly or has decreased in the last decades, suggesting that psychogenic ED is on the rise [3]. The DSM-IV-TR defines some behaviors with hedonic qualities, such as gambling, shopping, sexual behaviors, Internet use, and video game use, as “impulse control disorders not elsewhere classified”—although these are often described as behavioral addictions [4]. Recent investigation has suggested the role of behavioral addiction in sexual dysfunctions: alterations in neurobiological pathways involved in sexual response might be a consequence of repeated, supernormal stimuli of various origins.

Among behavioral addictions, problematic Internet use and online pornography consumption are often cited as possible risk factors for sexual dysfunction, often with no definite boundary between the two phenomena. Online users are attracted to Internet pornography because of its anonymity, affordability, and accessibility, and in many cases its usage could lead users through a cybersex addiction: in these cases, users are more likely to forget the “evolutionary” role of sex, finding more excitement in self-selected sexually explicit material than in intercourse.

In literature, researchers are discordant about positive and negative function of online pornography. From the negative perspective, it represents the principal cause of compulsive masturbatory behavior, cybersex addiction, and even erectile dysfunction….

19) Neurocognitive mechanisms in compulsive sexual behavior disorder (2018) – Excerpt:

To date, most neuroimaging research on compulsive sexual behavior has provided evidence of overlapping mechanisms underlying compulsive sexual behavior and non-sexual addictions. Compulsive sexual behavior is associated with altered functioning in brain regions and networks implicated in sensitization, habituation, impulse dyscontrol, and reward processing in patterns like substance, gambling, and gaming addictions. Key brain regions linked to CSB features include the frontal and temporal cortices, amygdala, and striatum, including the nucleus accumbens.

CSBD has been included in the current version of theICD-11 as an impulse-control disorder [39]. As described by the WHO, ‘Impulse-control disorders are characterized by the repeated failure to resist an impulse, drive, or urge to perform an act that is rewarding to the person, at least in the short-term, despite consequences such as longer-term harm either to the individual or to others, marked distress about the behaviour pattern, or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning’ [39]. Current findings raise important questions regarding the classification of CSBD. Many disorders characterized by impaired impulse-control are classified elsewhere in the ICD-11 (for example, gambling, gaming, and substance-use disorders are classified as being addictive disorders) [123].

20) A Current Understanding of the Behavioral Neuroscience of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder and Problematic Pornography Use – Excerpts:

Recent neurobiological studies have revealed that compulsive sexual behaviors are associated with altered processing of sexual material and differences in brain structure and function.

The findings summarized in our overview suggest relevant similarities with behavioral and substance-related addictions, which share many abnormalities found for CSBD (as reviewed in [127]). Although beyond the scope of the present report, substance and behavioral addictions are characterized by altered cue reactivity indexed by subjective, behavioral, and neurobiological measures (overviews and reviews: [128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133]; alcohol: [134, 135]; cocaine: [136, 137]; tobacco: [138, 139]; gambling: [140, 141]; gaming: [142, 143]). Results concerning resting-state functional connectivity show similarities between CSBD and other addictions [144, 145].

Although few neurobiological studies of CSBD have been conducted to date, existing data suggest neurobiological abnormalities share communalities with other additions such as substance use and gambling disorders. Thus, existing data suggest that its classification may be better suited as a behavioral addiction rather than an impulse-control disorder.

21) Ventral Striatal Reactivity in Compulsive Sexual Behaviors (2018) – Excerpts:

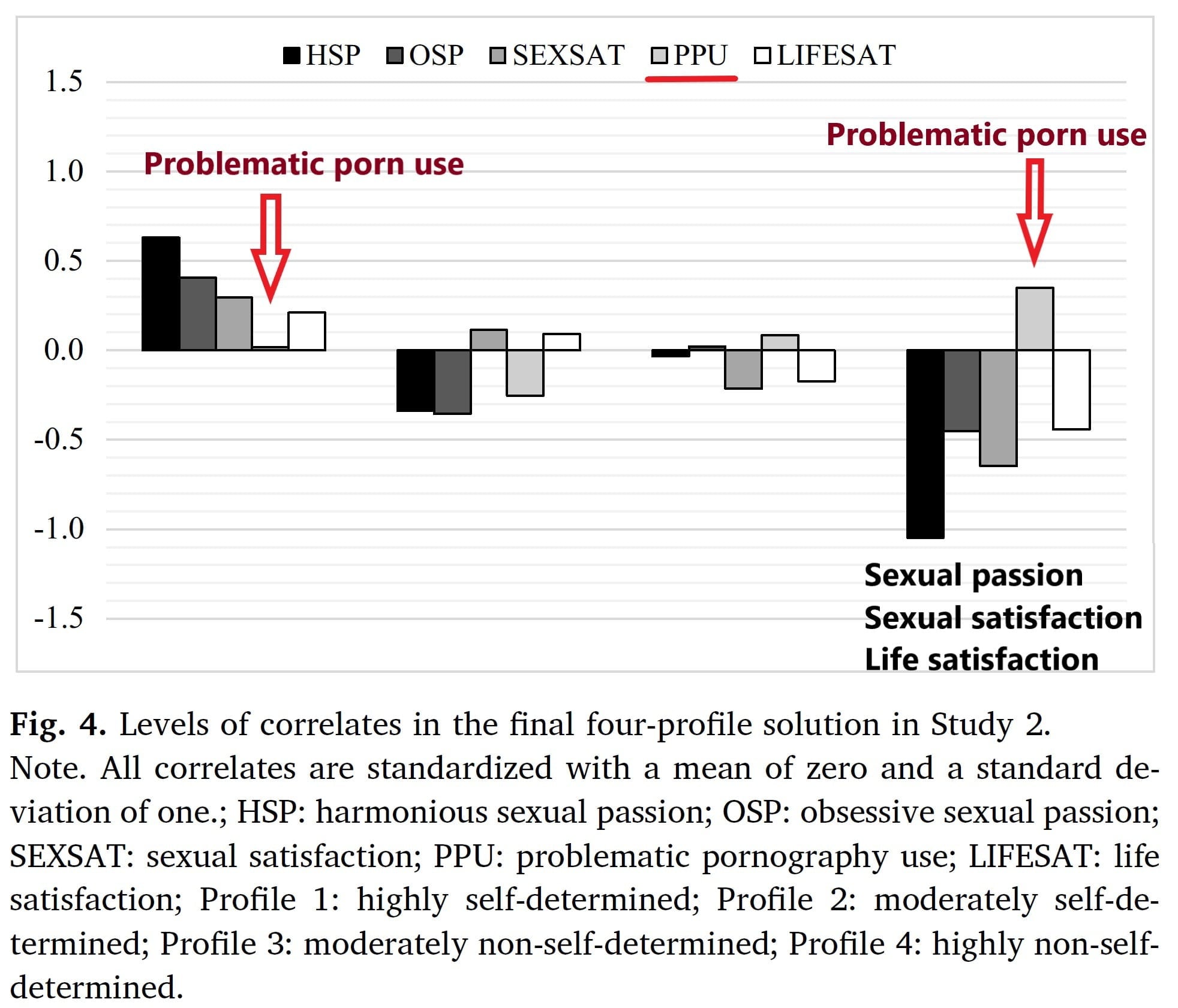

Compulsive Sexual Behaviors (CSB) are a reason to seek treatment. Given this reality, the number of studies on CSB has increased substantially in the last decade and the World Health Organization (WHO) included CSB in its proposal for the upcoming ICD-11…… From our point of view, it is worth investigating whether CSB can be distinguished into two subtypes characterized by: (1) dominant interpersonal sexual behaviors, and (2) dominant solitary sexual behaviors and pornography watching (48, 49).

The amount of available studies on CSB (and sub-clinical populations of frequent pornography users) is constantly increasing. Among currently available studies, we were able to find nine publications (Table 1) which utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging. Only four of these (36–39) directly investigated processing of erotic cues and/or rewards and reported findings related to ventral striatum activations. Three studies indicate increased ventral striatal reactivity for erotic stimuli (36–39) or cues predicting such stimuli (36–39). These findings are consistent with Incentive Salience Theory (IST) (28), one of the most prominent frameworks describing brain functioning in addiction. The only support for another theoretical framework which predicts hypoactivation of the ventral striatum in addiction, RDS theory (29, 30), comes partially from one study (37), where individuals with CSB presented lower ventral striatal activation for exciting stimuli when compared to controls.

22) Oline Porn Addiction: What We Know and What We Don’t—A Systematic Review (2019) – Excerpts:

In the last few years, there has been a wave of articles related to behavioral addictions; some of them have a focus on online pornography addiction. However, despite all efforts, we are still unable to profile when engaging in this behavior becomes pathological. Common problems include: sample bias, the search for diagnostic instrumentals, opposing approximations to the matter, and the fact that this entity may be encompassed inside a greater pathology (i.e., sex addiction) that may present itself with very diverse symptomatology. Behavioral addictions form a largely unexplored field of study, and usually exhibit a problematic consumption model: loss of control, impairment, and risky use. Hypersexual disorder fits this model and may be composed of several sexual behaviors, like problematic use of online pornography (POPU). Online pornography use is on the rise, with a potential for addiction considering the “triple A” influence (accessibility, affordability, anonymity). This problematic use might have adverse effects in sexual development and sexual functioning, especially among the young population.

As far as we know, a number of recent studies support this entity as an addiction with important clinical manifestations such as sexual dysfunction and psychosexual dissatisfaction. Most of the existing work is based off on similar research done on substance addicts, based on the hypothesis of online pornography as a ‘supranormal stimulus’ akin to an actual substance that, through continued consumption, can spark an addictive disorder. However, concepts like tolerance and abstinence are not yet clearly established enough to merit the labeling of addiction, and thus constitute a crucial part of future research. For the moment, a diagnostic entity encompassing out of control sexual behavior has been included in the ICD-11 due to its current clinical relevance, and it will surely be of use to address patients with these symptoms that ask clinicians for help.

23) Occurrence and development of online porn addiction: individual susceptibility factors, strengthening mechanisms and neural mechanisms (2019) – Excerpts:

Initiation and development of cybersex addiction have two stages with classical conditioning and operant conditioning. Firstly, individuals use cybersex occasionally out of entertainment and curiosity. On this stage, use of internet devices is paired with sexual arousal and The results in classical conditioning, further leads to sensitization of cybersex-related cues which trigger intense craving. Individual vulnerabilities also facilitate sensitization of cybersex-related cues. On the second stage, individuals make use of cybersex frequently to satisfy their sexual desires or During this process, cybersex-related cognitive bias like positive expectation of cybersex and coping mechanism like using it to deal with negative emotions are positively reinforced, those personal traits associated with cybersex addiction such as narcissism, sexual sensation seeking, sexual excitability, dysfunction use of sex are also positively reinforced, while common personality disorders like nervousness, low self-esteem and psychopathologies like depression, anxiety are negatively reinforced. Executive function deficits occur due to long-term cybersex use. Interaction of executive function deficits and intense craving promotes development and maintenance Of cybersex addiction. Researches using electrophysiological and brain imaging tools mainly to study cybersex addiction found that cybersex addicts may develop more and more robust craving for cybersex when facing cybersex-related cues, but they feel less and less pleasant when using it. Studies provide evidence for intense craving triggered by cybersex-related cues and impaired executive function. In conclusion, people who are vulnerable to cybersex addiction can’t stop cybersex use out of more and more intense craving for cybersex and impaired executive function, but they feel less and less satisfied when using it, and search for more and more original pornographic materials online at the cost of plenty of time and money. Once they reduce cybersex use or just quit it, they would suffer from a series of adverse effects like depression, anxiety, erection dysfunction, lack of sexual arousal.

24) Theories, prevention, and treatment of pornography-use disorder (2019)– Excerpts:

Compulsive sexual behavior disorder, including problematic pornography use, has been included in the ICD-11 as impulse control disorder. The diagnostic criteria for this disorder, however, are very similar to the criteria for disorders due to addictive behaviors, for example repetitive sexual activities becoming a central focus of the personʼs life, unsuccessful efforts to significantly reduce repetitive sexual behaviors and continued repetitive sexual behaviors despite experiencing negative consequences (WHO, 2019). Many researchers and clinicians also argue that problematic pornography use can be considered a behavioral addiction.

Cue-reactivity and craving in combination with reduced inhibitory control, implicit cognitions (e.g. approach tendencies) and experiencing gratification and compensation linked to pornography use have been demonstrated in individuals with symptoms of pornography-use disorder. Neuroscientific studies confirm the involvement of addiction-related brain circuits, including the ventral striatum and other parts of fronto-striatal loops, in the development and maintenance of problematic pornography use. Case reports and proof-of-concept studies suggest the efficacy of pharmacological interventions, for example the opioid antagonist naltrexone, for treating individuals with pornography-use disorder and compulsive sexual behavior disorder.

Theoretical considerations and empirical evidence suggest that the psychological and neurobiological mechanisms involved in addictive disorders are also valid for pornography-use disorder.

25) Self-perceived Problematic Pornography Use: An Integrative Model from a Research Domain Criteria and Ecological Perspective (2019) – Excerpts

Self-perceived problematic pornography use seems to be related to multiple units of analysis and different systems in the organism. Based on the findings within the RDoC paradigm described above, it is possible to create a cohesive model in which different units of analysis impact each other (Fig. 1). It appears that elevated levels of dopamine, present in the natural activation of the reward system related to sexual activity and orgasm, interfere with the regulation of the VTA-NAc system in people who report SPPPU. This dysregulation leads to greater activation of the reward system and increased conditioning related to the use of pornography, fostering approach behavior to pornographic material due to the increase in dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. Continued exposure to immediate and easily available pornographic material seems to create an imbalance in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system. This excess dopamine activates GABA output pathways, producing dynorphin as a byproduct, which inhibits dopamine neurons. When dopamine decreases, acetylcholine is released and can generate an aversive state (Hoebel et al. 2007), creating the negative reward system found in the second stage of addiction models. This imbalance is also correlated to the shift from approach to avoidance behavior, seen in people who report problematic pornography use…. These changes in internal and behavioral mechanisms among people with SPPPU are similar to those observed in people with substance addictions, and map into models of addiction (Love et al. 2015).

26) Cybersex addiction: an overview of the development and treatment of a newly emerging disorder (2020) – Excerpts:

Cybersex addiction is a non-substance related addiction that involves online sexual activity on the internet. Nowadays, various kinds of things related to sex or pornography are easily accessible through internet media. In Indonesia, sexuality is usually assumed taboo but most young people have been exposed to pornography. It can lead to an addiction with many negative effects on users, such as relationships, money, and psychiatric problems like major depression and anxiety disorders.

27) Which Conditions Should Be Considered as Disorders in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) Designation of “Other Specified Disorders Due to Addictive Behaviors”? (2020) – A review by addiction experts concludes that pornography-use disorder is a condition that ought to be diagnosed with the ICD-11 category “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”. In other words, compulsive porn use looks like other recognized addictions. Excerpts:

Compulsive sexual behavior disorder, as has been included in the ICD-11 category of impulse-control disorders, may include a broad range of sexual behaviors including excessive viewing of pornography that constitutes a clinically relevant phenomenon (Brand, Blycker, & Potenza, 2019; Kraus et al., 2018). The classification of compulsive sexual behavior disorder has been debated (Derbyshire & Grant, 2015), with some authors suggesting that the addiction framework is more appropriate (Gola & Potenza, 2018), which can be particularly the case for individuals suffering specifically from problems related to pornography use and not from other compulsive or impulsive sexual behaviors (Gola, Lewczuk, & Skorko, 2016; Kraus, Martino, & Potenza, 2016).

The diagnostic guidelines for gaming disorder share several features with those for compulsive sexual behavior disorder and may potentially be adopted by changing “gaming” to “pornography use.” These three core features have been considered central to problematic pornography use (Brand, Blycker, et al., 2019) and appear to fit appropriately the basic considerations (Fig. 1). Several studies have demonstrated the clinical relevance (criterion 1) of problematic pornography use, leading to functional impairment in daily life including jeopardizing work and personal relationships, and justifying treatment (Gola & Potenza, 2016; Kraus, Meshberg-Cohen, Martino, Quinones, & Potenza, 2015; Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016). In several studies and review articles, models from the addiction research (criterion 2) have been used to derive hypotheses and to explain the results (Brand, Antons, Wegmann, & Potenza, 2019; Brand, Wegmann, et al., 2019; Brand, Young, et al., 2016; Stark et al., 2017; Wéry, Deleuze, Canale, & Billieux, 2018). Data from self-report, behavioral, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging studies demonstrate an involvement of psychological processes and underlying neural correlates that have been investigated and established to varying degrees for substance-use disorders and gambling/gaming disorders (criterion 3). Commonalities noted in prior studies include cue-reactivity and craving accompanied by increased activity in reward-related brain areas, attentional biases, disadvantageous decision-making, and (stimuli-specific) inhibitory control (e.g., Antons & Brand, 2018; Antons, Mueller, et al., 2019; Antons, Trotzke, Wegmann, & Brand, 2019; Bothe et al., 2019; Brand, Snagowski, Laier, & Maderwald, 2016; Gola et al., 2017; Klucken, Wehrum-Osinsky, Schweckendiek, Kruse, & Stark, 2016; Kowalewska et al., 2018; Mechelmans et al., 2014; Stark, Klucken, Potenza, Brand, & Strahler, 2018; Voon et al., 2014).

Based on evidence reviewed with respect to the three meta-level-criteria proposed, we suggest that pornography-use disorder is a condition that may be diagnosed with the ICD-11 category “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors” based on the three core criteria for gaming disorder, modified with respect to pornography viewing (Brand, Blycker, et al., 2019). One conditio sine qua non for considering pornography-use disorder within this category would be that the individual suffers solely and specifically from diminished control over pornography consumption (nowadays online pornography in most cases), which is not accompanied by further compulsive sexual behaviors (Kraus et al., 2018). Further, the behavior should be considered as an addictive behavior only if it is related to functional impairment and experiencing negative consequences in daily life, as it is also the case for gaming disorder (Billieux et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2019). However, we also note that pornography-use disorder may currently be diagnosed with the current ICD-11 diagnosis of compulsive sexual behavior disorder given that pornography viewing and the frequently accompanying sexual behaviors (most frequently masturbation but potentially other sexual activities including partnered sex) may meet the criteria for compulsive sexual behavior disorder (Kraus & Sweeney, 2019). The diagnosis of compulsive sexual behavior disorder may fit for individuals who not only use pornography addictively, but who also suffer from other non-pornography-related compulsive sexual behaviors. The diagnosis of pornography-use disorder as other specified disorder due to addictive behaviors may be more adequate for individuals who exclusively suffer from poorly controlled pornography viewing (in most cases accompanied by masturbation). Whether or not a distinction between online and offline pornography use may be useful is currently debated, which is also the case for online/offline gaming (Király & Demetrovics, 2017).

28) The Addictive Nature of Compulsive Sexual Behaviours and Problematic Online Pornography Consumption: A Review (2020) – Excerpts:

Available findings suggest that there are several features of CSBD and POPU that are consistent with characteristics of addiction, and that interventions helpful in targeting behavioural and substance addictions warrant consideration for adaptation and use in supporting individuals with CSBD and POPU. While there are no randomized trials of treatments for CSBD or POPU, opioid antagonists, cognitive behavioural therapy, and mindfulness-based intervention appear to show promise on the basis of some case reports.

The neurobiology of POPU and CSBD involves a number of shared neuroanatomical correlates with established substance use disorders, similar neuropsychological mechanisms, as well as common neurophysiological alterations in the dopamine reward system.

Several studies have cited shared patterns of neuroplasticity between sexual addiction and established addictive disorders.

Mirroring excessive substance use, the use of excessive pornography has a negative impact on several domains of functioning, impairment and distress.

29) Dysfunctional sexual behaviors: definition, clinical contexts, neurobiological profiles and treatments (2020) – Excerpts:

1. The use of pornography among young people, who use it massively online, is connected to the decrease in sexual desire and premature ejaculation, as well as in some cases to social anxiety disorders, depression, DOC, and ADHD [30-32].

2. There is a clear neurobiological difference between “sexual employees” and “porn addicts”: if the former has a ventral hypoactivity, the latter instead are characterized by greater ventral reactivity for erotic signals and rewards without hypoactivity of the reward circuits. This would suggest that employees need interpersonal physical contact, while the latter tend to solitary activity [33,34]. Also, drug addicts exhibit greater disorganization of the white matter of the prefrontal cortex [35].

3. Porn addiction, although distinct neurobiologically from sexual addiction, is still a form of behavioral addiction and this dysfunctionality favors an aggravation of the person’s psychopathological condition, directly and indirectly involving a neurobiological modification at the level of desensitization to functional sexual stimulus, hypersensitization to stimulus sexual dysfunction, a marked level of stress capable of affecting the hormonal values of the pituitary-hypothalamic-adrenal axis and hypofrontality of the prefrontal circuits [36].

4. The low tolerance of pornography consumption was confirmed by an fMRI study which found a lower presence of gray matter in the reward system (dorsal striatum) related to the quantity of pornography consumed. He also found that increased use of pornography is correlated with less activation of the reward circuit while briefly watching sexual photos. Researchers believe their results indicated desensitization and possibly tolerance, which is the need for more stimulation to achieve the same level of arousal. Furthermore, signals of lower potential have been found in Putamen in porn-dependent subjects [37].

5. Contrary to what one might think, porn addicts do not have a high sexual desire and the masturbatory practice associated with viewing pornographic material decreases the desire also favoring premature ejaculation, as the subject feels more comfortable in solo activity. Therefore individuals with greater reactivity to porn prefer to perform solitary sexual acts than shared with a real person [38,39].

6. The sudden suspension of porn addiction causes negative effects in mood, excitement, and relational and sexual satisfaction [40,41].

7. The massive use of pornography facilitates the onset of psychosocial disorders and relationship difficulties [42].

8. The neural networks involved in sexual behavior are similar to those involved in processing other rewards, including addictions.

30) What should be included in the criteria for compulsive sexual behavior disorder? (2020) – This important paper based on recent research, gently corrects some of the misleading porn research claims. Among the highlights, the authors take on the disingenuous “moral incongruence” concept so popular with pro-porn researchers. Also see the helpful chart comparing Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder and the ill-fated DSM-5 Hypersexual Disorder proposal. Excerpts:

Diminished pleasure derived from sexual behavior may also reflect tolerance related to repetitive and excessive exposure to sexual stimuli, which are included in addiction models of CSBD (Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016) and supported by neuroscientific findings (Gola & Draps, 2018). An important role for tolerance relating to problematic pornography use is also suggested in community and subclinical samples (Chen et al., 2021). …

The classification of CSBD as an impulse control disorder also warrants consideration. … Additional research may help refine the most appropriate classification of CSBD as happened with gambling disorder, reclassified from the category of impulse control disorders to non-substance or behavioral addictions in DSM-5 and ICD-11. … impulsivity may not contribute as strongly to problematic pornography use as some have proposed (Bőthe et al., 2019).

…Feelings of moral incongruence should not arbitrarily disqualify an individual from receiving a diagnosis of CSBD. For example, viewing of sexually explicit material that is not in alignment with one’s moral beliefs (for example, pornography that includes violence towards and objectification of women (Bridges et al., 2010), racism (Fritz, Malic, Paul, & Zhou, 2020), themes of rape and incest (Bőthe et al., 2021; Rothman, Kaczmarsky, Burke, Jansen, & Baughman, 2015) may be reported as morally incongruent, and objectively excessive viewing of such material may also result in impairment in multiple domains (e.g., legal, occupational, personal and familial). Also, one may feel moral incongruence about other behaviors (e.g., gambling in gambling disorder or substance use in substance use disorders), yet moral incongruence is not considered in the criteria for conditions related to these behaviors, even though it may warrant consideration during treatment (Lewczuk, Nowakowska, Lewandowska, Potenza, & Gola, 2020). …

31) Decision-Making in Gambling Disorder, Problematic Pornography Use, and Binge-Eating Disorder: Similarities and Differences (2021) – The review provides an overview of the neurocognitive mechanisms of gambling disorder (GD), problematic pornography use (PPU), and binge-eating disorder (BED), focusing specifically on decision-making processes related to executive functioning (prefrontal cortex). Excerpts:

Common mechanisms underlying substance-use disorders (SUDs such as alcohol, cocaine, and opioids) and addictive or maladaptative disorders or behaviors (such as GD and PPU) have been suggested [5,6,7,8, 9••]. Shared underpinnings between addictions and EDs have also been described, mainly including top-down cognitive-control [10,11,12] and bottom-up reward-processing [13, 14] alterations. Individuals with these disorders often show impaired cognitive control and disadvantageous decision-making [12, 15,16,17]. Deficits in decision-making processes and goal-directed learning have been found across multiple disorders; thus, they could be considered clinically relevant transdiagnostic features [18,19,20]. More specifically, it has been suggested that these processes are found in individuals with behavioral addictions (e.g., in dual-process and other models of addictions) [21,22,23,24].

Similarities between CSBD and addictions have been described, and impaired control, persistent use despite adverse consequences, and tendencies to engage in risky decisions may be shared features (37••, 40).

Understanding decision-making has important implications for the assessment and treatment of individuals with GD, PPU, and BED. Similar alterations in decision-making under risk and ambiguity, as well as greater delay discounting, have been reported in GD, BED, and PPU. These findings support a transdiagnostic feature that may be amenable to interventions for the disorders.

32) Which Conditions Should Be Considered as Disorders in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) Designation of “Other Specified Disorders Due to Addictive Behaviors”? (2020) – A review by addiction experts concludes that pornography-use disorder is a condition that may be diagnosed with the ICD-11 category “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”. In other words, compulsive porn use looks like other recognized behavioral addictions, which include gambling and gaming disorders. Excerpts –

Note that we are not suggesting the inclusion of new disorders in the ICD-11. Rather, we aim to emphasize that some specific potentially addictive behaviors are discussed in the literature, which are currently not included as specific disorders in the ICD-11, but which may fit the category of “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors” and consequently may be coded as 6C5Y in clinical practice. (emphasis supplied)…

Based on evidence reviewed with respect to the three meta-level-criteria proposed, we suggest that pornography-use disorder is a condition that may be diagnosed with the ICD-11 category “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors” based on the three core criteria for gaming disorder, modified with respect to pornography viewing (Brand, Blycker, et al., 2019)….

The diagnosis of pornography-use disorder as other specified disorder due to addictive behaviors may be more adequate for individuals who exclusively suffer from poorly controlled pornography viewing (in most cases accompanied by masturbation).

33) Cognitive processes related to problematic pornography use (PPU): A systematic review of experimental studies (2021) – Excerpts:

Some people experience symptoms and negative outcomes derived from their persistent, excessive, and problematic engagement in pornography viewing (i.e., Problematic Pornography Use, PPU). Recent theoretical models have turned to different cognitive processes (e.g., inhibitory control, decision making, attentional bias, etc.) to explain the development and maintenance of PPU.

In the current paper, we review and compile the evidence derived from 21 studies investigating the cognitive processes underlying PPU. In brief, PPU is related to: (a) attentional biases toward sexual stimuli, (b) deficient inhibitory control (in particular, to problems with motor response inhibition and to shift attention away from irrelevant stimuli), (c) worse performance in tasks assessing working memory, and (d) decision making impairments (in particular, to preferences for short-term small gains rather than long-term large gains, more impulsive choice patterns than non-erotica users, approach tendencies toward sexual stimuli, and inaccuracies when judging the probability and magnitude of potential outcomes under ambiguity). Some of this findings are derived from studies in clinical samples of patients with PPU or with a diagnosis of SA/HD/CSBD and PPU as their primary sexual problem (e.g., Mulhauser et al., 2014, Sklenarik et al., 2019), suggesting that these distorted cognitive processes may constitute ‘sensitive’ indicators of PPU.

At a theoretical level, the results of this review support the relevance of the main cognitive components of the I-PACE model (Brand et al., 2016, Sklenarik et al., 2019).

34) PDF of full review: Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder – the evolution of a new diagnosis introduced to the ICD-11, current evidence and ongoing research challenges (2021) – Abstract:

In 2019 Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD) has been officially included in the forthcoming 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases published by the World Health Organization (WHO). The placement of CSBD as a new disease entity was preceded by a three-decade-long discussion on the conceptualization of these behaviors. Despite the potential benefits of WHO’s decisions, the controversy around this topic has not ceased. Both clinicians and scientists are still debating on gaps in the current knowledge regarding the clinical picture of people with CSBD, and the neural and psychological mechanisms underlying this problem. This article provides an overview of the most important issues related to the formation of CSBD as a separate diagnostic unit in the classifications of mental disorders (such as DSM and ICD), as well as a summary of the major controversies related to the current classification of CSBD.

See Questionable & Misleading Studies for highly publicized papers that are not what they claim to be (this outdated paper – Ley, et al., 2014 – was not a literature review and misrepresented most the papers it did cite).

Neurological Studies (fMRI, MRI, EEG, Neuro-endocrine, Neuro-pyschological):

The neurological studies below are categorized in two ways. First by the addiction-related brain changes each reported. Below that the same studies are listed by date of publication, with excerpts and clarifications.

Lists by addiction-related brain change: The four major brain changes induced by addiction are described by George F. Koob and Nora D. Volkow in their landmark review. Koob is the Director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and Volkow is the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). It was published in The New England Journal of Medicine: Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction (2016). The paper describes the major brain changes involved with both drug and behavioral addictions, while stating in its opening paragraph that sex addiction exists:

“We conclude that neuroscience continues to support the brain disease model of addiction. Neuroscience research in this area not only offers new opportunities for the prevention and treatment of substance addictions and related behavioral addictions (e.g., to food, sex, and gambling)….”

The Volkow & Koob paper outlined four fundamental addiction-caused brain changes, which are: 1) Sensitization, 2) Desensitization, 3) Dysfunctional prefrontal circuits (hypofrontality), 4) Malfunctioning stress system. All 4 of these brain changes have been identified among the many neurological studies listed on this page:

- Studies reporting sensitization (cue-reactivity & cravings) in porn users/sex addicts: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24.

- Studies reporting desensitization or habituation (resulting in tolerance) in porn users/sex addicts: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

- Studies reporting poorer executive functioning (hypofrontality) or altered prefrontal activity in porn users/sex addicts: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17.

- Studies indicating a dysfunctional stress system in porn users/sex addicts: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Lists by date of publication: The following list contains all the neurological studies published on porn users and sex addicts. Each study listed below is accompanied by a description or excerpt, and indicates which of the 4 addiction-related brain change(s) just discussed its findings endorse:

1) Preliminary Investigation of The Impulsive And Neuroanatomical Characteristics of Compulsive Sexual Behavior (Miner et al., 2009) – [dysfunctional prefrontal circuits/poorer executive function] – fMRI study involving primarily sex addicts. Study reports more impulsive behavior in a Go-NoGo task in sex addicts (hypersexuals) compared to control participants. Brain scans revealed that sex addicts had disorganized prefrontal cortex white matter compared to controls. Excerpts:

In addition to the above self-report measures, CSB patients also showed significantly more impulsivity on a behavioral task, the Go-No Go procedure.

Results also indicate that CSB patients showed significantly higher superior frontal region mean diffusivity (MD) than controls. A correlational analysis indicated significant associations between impulsivity measures and inferior frontal region fractional anisotrophy (FA) and MD, but no associations with superior frontal region measures. Similar analyses indicated a significant negative association between superior frontal lobe MD and the compulsive sexual behavior inventory.

2) Self-reported differences on measures of executive function and hypersexual behavior in a patient and community sample of men (Reid et al., 2010) – [poorer executive function] – An excerpt:

Patients seeking help for hypersexual behavior often exhibit features of impulsivity, cognitive rigidity, poor judgment, deficits in emotion regulation, and excessive preoccupation with sex. Some of these characteristics are also common among patients presenting with neurological pathology associated with executive dysfunction. These observations led to the current investigation of differences between a group of hypersexual patients (n = 87) and a non-hypersexual community sample (n = 92) of men using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Adult Version Hypersexual behavior was positively correlated with global indices of executive dysfunction and several subscales of the BRIEF-A. These findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the hypothesis that executive dysfunction may be implicated in hypersexual behavior.

3) Watching Pornographic Pictures on the Internet: Role of Sexual Arousal Ratings and Psychological-Psychiatric Symptoms for Using Internet Sex Sites Excessively (Brand et al., 2011) – [greater cravings/sensitization and poorer executive function] – An excerpt:

Results indicate that self-reported problems in daily life linked to online sexual activities were predicted by subjective sexual arousal ratings of the pornographic material, global severity of psychological symptoms, and the number of sex applications used when being on Internet sex sites in daily life, while the time spent on Internet sex sites (minutes per day) did not significantly contribute to explanation of variance in IATsex score. We see some parallels between cognitive and brain mechanisms potentially contributing to the maintenance of excessive cybersex and those described for individuals with substance dependence.

4) Pornographic Picture Processing Interferes with Working Memory Performance (Laier et al., 2013) – [greater cravings/sensitization and poorer executive function] – An excerpt:

Some individuals report problems during and after Internet sex engagement, such as missing sleep and forgetting appointments, which are associated with negative life consequences. One mechanism potentially leading to these kinds of problems is that sexual arousal during Internet sex might interfere with working memory (WM) capacity, resulting in a neglect of relevant environmental information and therefore disadvantageous decision making. Results revealed worse WM performance in the pornographic picture condition of the 4-back task compared with the three remaining picture conditions. Findings are discussed with respect to Internet addiction because WM interference by addiction-related cues is well known from substance dependencies.

5) Sexual Picture Processing Interferes with Decision-Making Under Ambiguity (Laier et al., 2013) – [greater cravings/sensitization and poorer executive function] – An excerpt:

Decision-making performance was worse when sexual pictures were associated with disadvantageous card decks compared to performance when the sexual pictures were linked to the advantageous decks. Subjective sexual arousal moderated the relationship between task condition and decision-making performance. This study emphasized that sexual arousal interfered with decision-making, which may explain why some individuals experience negative consequences in the context of cybersex use.

6) Cybersex addiction: Experienced sexual arousal when watching pornography and not real-life sexual contacts makes the difference (Laier et al., 2013) – [greater cravings/sensitization and poorer executive function] – An excerpt:

The results show that indicators of sexual arousal and craving to Internet pornographic cues predicted tendencies towards cybersex addiction in the first study. Moreover, it was shown that problematic cybersex users report greater sexual arousal and craving reactions resulting from pornographic cue presentation. In both studies, the number and the quality with real-life sexual contacts were not associated to cybersex addiction. The results support the gratification hypothesis, which assumes reinforcement, learning mechanisms, and craving to be relevant processes in the development and maintenance of cybersex addiction. Poor or unsatisfying sexual real life contacts cannot sufficiently explain cybersex addiction.

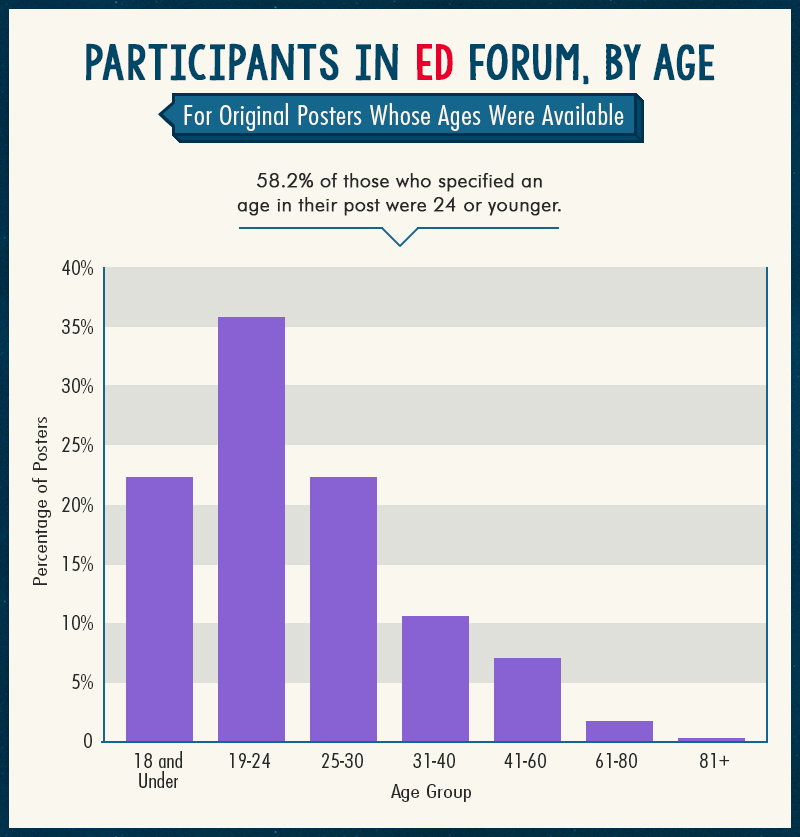

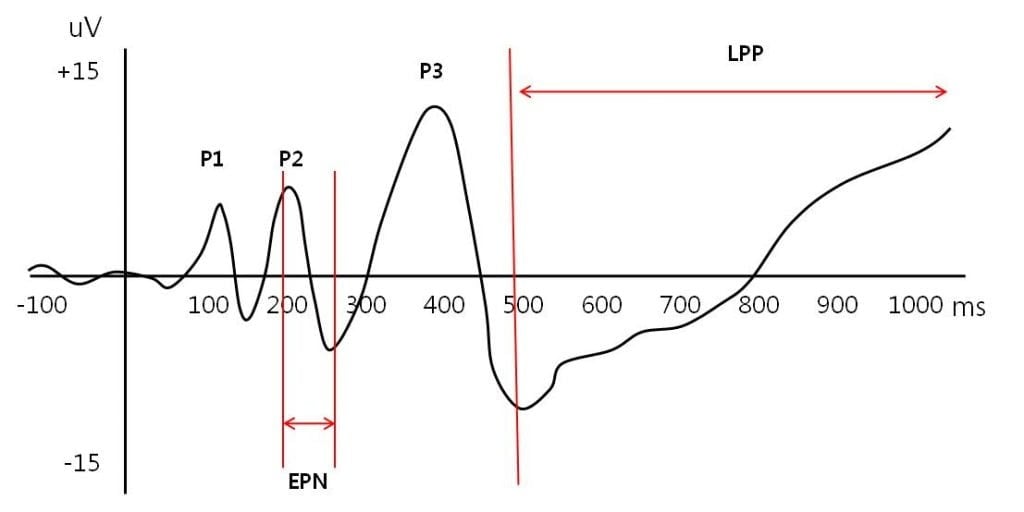

7) Sexual Desire, not Hypersexuality, is Related to Neurophysiological Responses Elicited by Sexual Images (Steele et al., 2013) – [greater cue-reactivity correlated with less sexual desire: sensitization and habituation] – This EEG study was touted in the media by spokesperson Nicole Prause as evidence against the existence of porn/sex addiction. Not so. Steele et al. 2013 actually lends support to the existence of both porn addiction and porn use down-regulating sexual desire. How so? The study reported higher EEG readings (relative to neutral pictures) when subjects were briefly exposed to pornographic photos. Studies consistently show that an elevated P300 occurs when addicts are exposed to cues (such as images) related to their addiction.

The often-repeated claims that subjects brains did not “respond like other addicts” is without support. This assertion is nowhere to be found in the actual study. It’s only found in Prause’s interviews.

In line with the Cambridge University brain scan studies, this EEG study also reported greater cue-reactivity to porn correlating with less desire for partnered sex. To put it another way – individuals with greater brain activation to porn would rather masturbate to porn than have sex with a real person. Shockingly, study spokesperson Nicole Prause claimed that porn users merely had “high libido,” yet the results of the study say the exact opposite (subjects’ desire for partnered sex was dropping in relation to their porn use). Seven peer-reviewed papers explain the truth: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. For more read an extensive critique.

Aside from the many unsupported claims in the press, it’s disturbing that Prause’s 2013 EGG study passed peer-review, as it suffered from serious methodological flaws: 1) subjects were heterogeneous (males, females, non-heterosexuals); 2) subjects were not screened for mental disorders or addictions; 3) study had no control group for comparison; 4) questionnaires were not validated for porn addiction.

Steele at al. is so badly flawed that only 4 of the above 20 literature reviews & commentaries bother to mention it: two critiquing it as unacceptable, while two cite it as correlating cue-reactivity with less desire for sex with a partner (signs of addiction).

8) Brain Structure and Functional Connectivity Associated With Pornography Consumption: The Brain on Porn (Kuhn & Gallinat, 2014) – [desensitization, habituation, and dysfunctional prefrontal circuits]. This Max Planck Institute fMRI study reported 3 neurological findings correlating with higher levels of porn use: (1) less reward system grey matter (dorsal striatum), (2) less reward circuit activation while briefly viewing sexual photos, (3) poorer functional connectivity between the dorsal striatum and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The researchers interpreted the 3 findings as an indication of the effects of longer-term porn exposure. Said the study,

This is in line with the hypothesis that intense exposure to pornographic stimuli results in a down-regulation of the natural neural response to sexual stimuli.

In describing the poorer functional connectivity between the PFC and the striatum the study said,

Dysfunction of this circuitry has been related to inappropriate behavioral choices, such as drug seeking, regardless of the potential negative outcome

Lead author Simone Kühn commenting in an article about the findings said:

We assume that subjects with a high porn consumption need increasing stimulation to receive the same amount of reward. That could mean that regular consumption of pornography more or less wears out your reward system. That would fit perfectly the hypothesis that their reward systems need growing stimulation.

9) Neural Correlates of Sexual Cue Reactivity in Individuals with and without Compulsive Sexual Behaviours (Voon et al., 2014) – [sensitization/cue-reactivity and desensitization] The first in a series of Cambridge University studies found the same brain activity pattern in porn addicts (CSB subjects) as seen in drug addicts and alcoholics – greater cue-reactivity or sensitization. Lead researcher Valerie Voon said:

There are clear differences in brain activity between patients who have compulsive sexual behaviour and healthy volunteers. These differences mirror those of drug addicts.

Voon et al., 2014 also found that porn addicts fit the accepted addiction model of wanting “it” more, but not liking “it” any more. Excerpt:

Compared to healthy volunteers, CSB subjects had greater subjective sexual desire or wanting to explicit cues and had greater liking scores to erotic cues, thus demonstrating a dissociation between wanting and liking

The researchers also reported that 60% of subjects (average age: 25) had difficulty achieving erections/arousal with real partners, yet could achieve erections with porn. This indicates sensitization or habituation. Excerpts:

CSB subjects reported that as a result of excessive use of sexually explicit materials….. experienced diminished libido or erectile function specifically in physical relationships with women (although not in relationship to the sexually explicit material)…

CSB subjects compared to healthy volunteers had significantly more difficulty with sexual arousal and experienced more erectile difficulties in intimate sexual relationships but not to sexually explicit material.

10) Enhanced Attentional Bias towards Sexually Explicit Cues in Individuals with and without Compulsive Sexual Behaviours (Mechelmans et al., 2014) – [sensitization/cue-reactivity] – The second Cambridge University study. An excerpt:

Our findings of enhanced attentional bias… suggest possible overlaps with enhanced attentional bias observed in studies of drug cues in disorders of addictions. These findings converge with recent findings of neural reactivity to sexually explicit cues in [porn addicts] in a network similar to that implicated in drug-cue-reactivity studies and provide support for incentive motivation theories of addiction underlying the aberrant response to sexual cues in [porn addicts]. This finding dovetails with our recent observation that sexually explicit videos were associated with greater activity in a neural network similar to that observed in drug-cue-reactivity studies. Greater desire or wanting rather than liking was further associated with activity in this neural network. These studies together provide support for an incentive motivation theory of addiction underlying the aberrant response towards sexual cues in CSB.

11) Cybersex addiction in heterosexual female users of internet pornography can be explained by gratification hypothesis (Laier et al., 2014) – [greater cravings/sensitization] – An excerpt:

We examined 51 female IPU and 51 female non-Internet pornography users (NIPU). Using questionnaires, we assessed the severity of cybersex addiction in general, as well as propensity for sexual excitation, general problematic sexual behavior, and severity of psychological symptoms. Additionally, an experimental paradigm, including a subjective arousal rating of 100 pornographic pictures, as well as indicators of craving, was conducted. Results indicated that IPU rated pornographic pictures as more arousing and reported greater craving due to pornographic picture presentation compared with NIPU. Moreover, craving, sexual arousal rating of pictures, sensitivity to sexual excitation, problematic sexual behavior, and severity of psychological symptoms predicted tendencies toward cybersex addiction in IPU. Being in a relationship, number of sexual contacts, satisfaction with sexual contacts, and use of interactive cybersex were not associated with cybersex addiction. These results are in line with those reported for heterosexual males in previous studies. Findings regarding the reinforcing nature of sexual arousal, the mechanisms of learning, and the role of cue reactivity and craving in the development of cybersex addiction in IPU need to be discussed.

12) Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations on Factors Contributing to Cybersex Addiction From a Cognitive Behavioral View (Laier et al., 2014) – [greater cravings/sensitization] – An excerpt:

The nature of a phenomenon often called cybersex addiction (CA) and its mechanisms of development are discussed. Previous work suggests that some individuals might be vulnerable to CA, while positive reinforcement and cue-reactivity are considered to be core mechanisms of CA development. In this study, 155 heterosexual males rated 100 pornographic pictures and indicated their increase of sexual arousal. Moreover, tendencies towards CA, sensitivity to sexual excitation, and dysfunctional use of sex in general were assessed. The results of the study show that there are factors of vulnerability to CA and provide evidence for the role of sexual gratification and dysfunctional coping in the development of CA.