Studies Reporting Withdrawal Symptoms in Porn Users

Pro-porn activists often assert porn addiction is a myth on the theory that compulsive porn users do not experience either tolerance (habituation, escalation) or withdrawal symptoms. Not so. In fact, not only do porn users and clinicians report both tolerance and withdrawal, over 60 studies report findings consistent with escalation of porn use (tolerance), habituation to porn, and even withdrawal symptoms (all signs and symptoms associated with addiction).

This page contains the growing list of peer-reviewed studies reporting withdrawal symptoms in porn users. Important to note: only a few studies have bothered to ask about withdrawal symptoms – perhaps due to the widespread denial that they exist. Yet the few research teams that have asked about withdrawal symptoms confirm their existence in porn users.

While recovering porn users are often startled by the severity of their withdrawal symptoms after they stop using porn, the fact is, withdrawal symptoms need not be present for someone to be diagnosed with addiction. First, you will find the language “neither tolerance nor withdrawal is necessary or sufficient for a diagnosis…” in both the DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5. Second, the oft-repeated sexology claim that “real” addictions cause severe, life-threatening withdrawal symptoms mistakenly conflates physiological dependence with addiction-related brain changes. An excerpt from this 2015 review of literature provides a technical explanation (Neuroscience of Internet Pornography Addiction: A Review and Update):

A key point of this stage is that withdrawal is not about the physiological effects from a specific substance. Rather, this model measures withdrawal via a negative affect resulting from the above process. Aversive emotions such as anxiety, depression, dysphoria, and irritability are indicators of withdrawal in this model of addiction [43,45]. Researchers opposed to the idea of behaviors being addictive often overlook or misunderstand this critical distinction, confusing withdrawal with detoxification [46,47].

In asserting that withdrawal symptoms must be present to diagnose an addiction, pro-porn activists (including numerous PhD’s) makes the rookie mistake of confusing physical dependency with addiction. These terms are not synonymous. Pro-porn PhD and former professor at Concordia Jim Pfaus made this same error in a 2016 article that YBOP critiqued: YBOP response to Jim Pfaus’s “Trust a scientist: sex addiction is a myth” January, 2016)

That said, internet porn research and numerous self-reports demonstrate that some porn users experience withdrawal and/or tolerance – which are also often characteristic of physical dependency. In fact, ex-porn users regularly report surprisingly severe withdrawal symptoms, which are reminiscent of drug withdrawals: insomnia, anxiety, irritability, mood swings, headaches, restlessness, poor concentration, fatigue, depression, and social paralysis, as well as the sudden loss of libido that guys call the ‘flatline’ (apparently unique to porn withdrawal).

Another sign of physical dependency reported by porn users is inability to get an erection or to have an orgasm without using porn. Empirical support arises from over 40 studies linking porn use/porn addiction to sexual problems and lower arousal (the first 7 studies in the list demonstrate causation, as participants eliminated porn use and healed chronic sexual dysfunctions).

Studies listed by date of publication

STUDY #1: Structural Therapy With a Couple Battling Pornography Addiction (2012) – Discusses both tolerance and withdrawal

Similarly, tolerance can also develop to pornography. After prolonged consumption of pornography, excitatory responses to pornography diminish; the repulsion evoked by common pornography fades and may be lost with prolonged consumption (Zillman, 1989). Thus, what initially led to an excitatory response does not necessarily lead to the same level of enjoyment of the frequently consumed material. There-fore, what aroused an individual initially may not arouse them in the later stages of their addiction. Because they do not achieve satisfaction or have the repulsion they once did, individuals addicted to pornography generally seek increasingly novel forms of pornography to achieve the same excitatory result.

For example, pornography addiction may begin with non-pornographic but provocative images and can then progress to more sexually explicit mages. As arousal diminishes with each use, an addicted individual may move on to more graphic forms of sexual images and erotica. As arousal again diminishes, the pattern continues to incorporate increasingly graphic, titillating, and detailed depictions of sexual activity through the various forms of media. Zillman (1989) states that prolonged pornography use can foster a preference for pornography featuring less common forms of sexuality (e.g., violence), and may alter perceptions of sexuality. Although this pattern typifies what one would expect to see with pornography addiction, not all pornography users experience this cascade into an addiction.

Withdrawal symptoms from pornography use may include depression, irritability, anxiety, obsessive thoughts, and an intense longing for pornography. Due to these often intense withdrawal symptoms, cessation from this reinforcement can be extremely difficult for both the individual and the couple’s relationship.

STUDY #2 – Consequences of Pornography Use (2017) – This study asked if internet users experienced anxiety when they couldn’t access porn on the internet (a withdrawal symptom): 24% experienced anxiety. One third of the participants had suffered negative consequences related to their porn use. Excerpts:

The objective of this study is to obtain a scientific and empirical approximation to the type of consumption of the Spanish population, the time they use in such consumption, the negative impact it has on the person and how anxiety is affected when it is not possible to access to it. The study has a sample of Spanish internet users (N = 2.408). An 8-item survey was developed through an online platform that provides information and psychological counselling on the harmful consequences of pornography consumption. To reach diffusion among the Spanish population, the survey was promoted through social networks and media.

The results show that one third of the participants had suffered negative consequences in family, social, academic or work environment. In addition, 33% spent more than 5 hours connected for sexual purposes, using pornography as a reward and 24% had anxiety symptoms if they could not connect.

STUDY #3: Out-of-control use of the internet for sexual purposes as behavioural addiction? – An upcoming study (presented at the 4th International Conference on Behavioral Addictions February 20–22, 2017) which asked about tolerance and withdrawal. It found both in “porn addicts.”

Anna Ševčíková1, Lukas Blinka1 and Veronika Soukalová1

1Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Background and aims:

There is an ongoing debate whether excessive sexual behaviour should be understood as a form of behavioural addiction (Karila, Wéry, Weistein et al., 2014). The present qualitative study aimed at analysing the extent to which out-of-control use of the internet for sexual purposes (OUISP) may be framed by the concept of behavioural addiction among those individuals who were in treatment due to their OUISP.

Methods:

We conducted in-depth interviews with 21 participants aged 22–54 years (Mage = 34.24 years). Using a thematic analysis, the clinical symptoms of OUISP were analysed with the criteria of behavioural addiction, with the special focus on tolerance and withdrawal symptoms (Griffiths, 2001).

Results:

The dominant problematic behaviour was out-of-control online pornography use (OOPU). Building up tolerance to OOPU manifested itself as an increasing amount of time spent on pornographic websites as well as searching for new and more sexually explicit stimuli within the non-deviant spectrum. Withdrawal symptoms manifested themselves on a psychosomatic level and took the form of searching for alternative sexual objects. Fifteen participants fulfilled all of the addiction criteria.

Conclusions:

The study indicates a usefulness for the behavioural addiction framework

STUDY #4: The Development of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS) (2017) – This paper developed and tested a problematic porn use questionnaire that was modeled after substance addiction questionnaires. Unlike previous porn addiction tests, this 18-item questionnaire assessed tolerance and withdrawal using the following 6 questions:

———-

Each question was scored from one to seven on a Likert scale: 1- Never, 2- Rarely, 3- Occasionally, 4- Sometimes, 5- Often, 6- Very Often, 7- All the Time. The graph below grouped porn users into 3 categories based on their total scores: “Nonprobelmatic,” “Low risk,” and “At risk.” The yellow line indicates no problems, which means that the “Low risk” and “At risk” porn users reported both tolerance and withdrawal. Put simply, this study actually asked about escalation (tolerance) and withdrawal – and both are reported by some porn users. End of debate.

STUDY #5: The Development and Validation of the Bergen-Yale Sex Addiction Scale With a Large National Sample (2018). This paper developed and tested a “sex addiction” questionnaire that was modeled after substance addiction questionnaires. As the authors explained, previous questionnaires have omitted key elements of addiction:

Most previous studies have relied on small clinical samples. The present study presents a new method for assessing sex addiction—the Bergen–Yale Sex Addiction Scale (BYSAS)—based on established addiction components (i.e., salience/craving, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict/problems, and relapse/loss of control).

The authors expand on the six established addiction components assessed, including tolerance and withdrawal.

The BYSAS was developed utilizing the six addiction criteria emphasized by Brown (1993), Griffiths (2005), and American Psychiatric Association (2013) encompassing salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflicts and relapse/loss of control…. In relation to sex addiction, these symptoms would be: salience/craving—over-preoccupation with sex or wanting sex, mood modification—excessive sex causing changes in mood, tolerance—increasing amounts of sex over time, withdrawal—unpleasant emotional/physical symptoms when not having sex, conflict—inter-/intrapersonal problems as a direct result of excessive sex, relapse—returning to previous patterns after periods with abstinence/control, and problems—impaired health and well-being arising from addictive sexual behavior.

The most prevalent “sex addiction” components seen in the subjects were salience/craving and tolerance, but the other components, including withdrawal, also showed up to a lesser degree:

Salience/craving and tolerance were more frequently endorsed in the higher rating category than other items, and these items had the highest factor loadings. This seems reasonable as these reflect less severe symptoms (e.g., question about depression: people score higher on feeling depressed, then they plan committing suicide). This may also reflect a distinction between engagement and addiction (often seen in the game addiction field)—where items tapping information about salience, craving, tolerance, and mood modification are argued to reflect engagement, whereas items tapping withdrawal, relapse and conflict more measure addiction. Another explanation could be that salience, craving, and tolerance may be more relevant and prominent in behavioral addictions than withdrawal and relapse.

This study, along with the preceding 2017 study that developed and validated the “Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale,” refutes the often-repeated claim that porn and sex addicts do not experience either tolerance or withdrawal symptoms.

STUDY #6: Technology-mediated addictive behaviors constitute a spectrum of related yet distinct conditions: A network perspective (2018) – Study assessed the overlap between 4 types of technology addiction: Internet, smartphone, gaming, cybersex. Found that each is a distinct addiction, yet all 4 involved withdrawal symptoms – including cybersex addiction. Excerpts:

To test the spectrum hypothesis and to have comparable symptoms for each technology-mediated behavior, the first and the last author linked each scale item with the following “classical” addiction symptoms: continued use, mood modification, loss of control, preoccupation, withdrawal, and consequences technology-mediated addictive behaviors were investigated using symptoms derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.) and the component model of addiction: Internet, smartphone, gaming, and cybersex.

Between-conditions edges often connected the same symptoms through Internet addiction symptoms. For example, Internet addiction withdrawal symptoms were connected with withdrawal symptoms of all other conditions (gaming addiction, smartphone addiction, and cybersex addiction) and adverse consequences of Internet addiction were also connected with adverse consequences of all other conditions.

STUDY #7: Prevalence, Patterns and Self-Perceived Effects of Pornography Consumption in Polish University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study (2019). The study reported everything the naysayers claim do not exist: tolerance/habituation, escalation of use, needing more extreme genres to be sexually aroused, withdrawal symptoms when quitting, porn-induced sexual problems, porn addiction, and more. A few excerpts related to tolerance/habituation/escalation:

The most common self-perceived adverse effects of pornography use included: the need for longer stimulation (12.0%) and more sexual stimuli (17.6%) to reach orgasm, and a decrease in sexual satisfaction (24.5%)…

The present study also suggests that earlier exposure may be associated with potential desensitization to sexual stimuli as indicated by a need for longer stimulation and more sexual stimuli required to reach orgasm when consuming explicit material, and overall decrease in sexual satisfaction…..

Various changes of pattern of pornography use occurring in the course of the exposure period were reported: switching to a novel genre of explicit material (46.0%), use of materials that do not match sexual orientation (60.9%) and need to use more extreme (violent) material (32.0%). The latter was more frequently reported by females considering themselves as curious compared tothose regarding themselves as uninquisitive

the present study found that a need to use more extreme pornography material was more frequently reported by males describing themselves as aggressive.

Additional signs of tolerance/escalation: needing multiple tabs open and using porn outside of home:

The majority of students admitted to use of private mode (76.5%, n = 3256) and multiple windows (51.5%, n = 2190) when browsing online pornography. Use of porn outside residence was declared by 33.0% (n = 1404).

Earlier age of first use related to greater problems and addiction (this indirectly indicates tolerance-habituation-escalation):

Age of first exposure to explicit material was associated with increased likelihood of negative effects of pornography in young adults—the highest odds were found for females and males exposed at 12 years or below. Although a cross-sectional study does not allow an assessment of causation, this finding may indeed indicate that childhood association with pornographic content may have long-term outcomes….

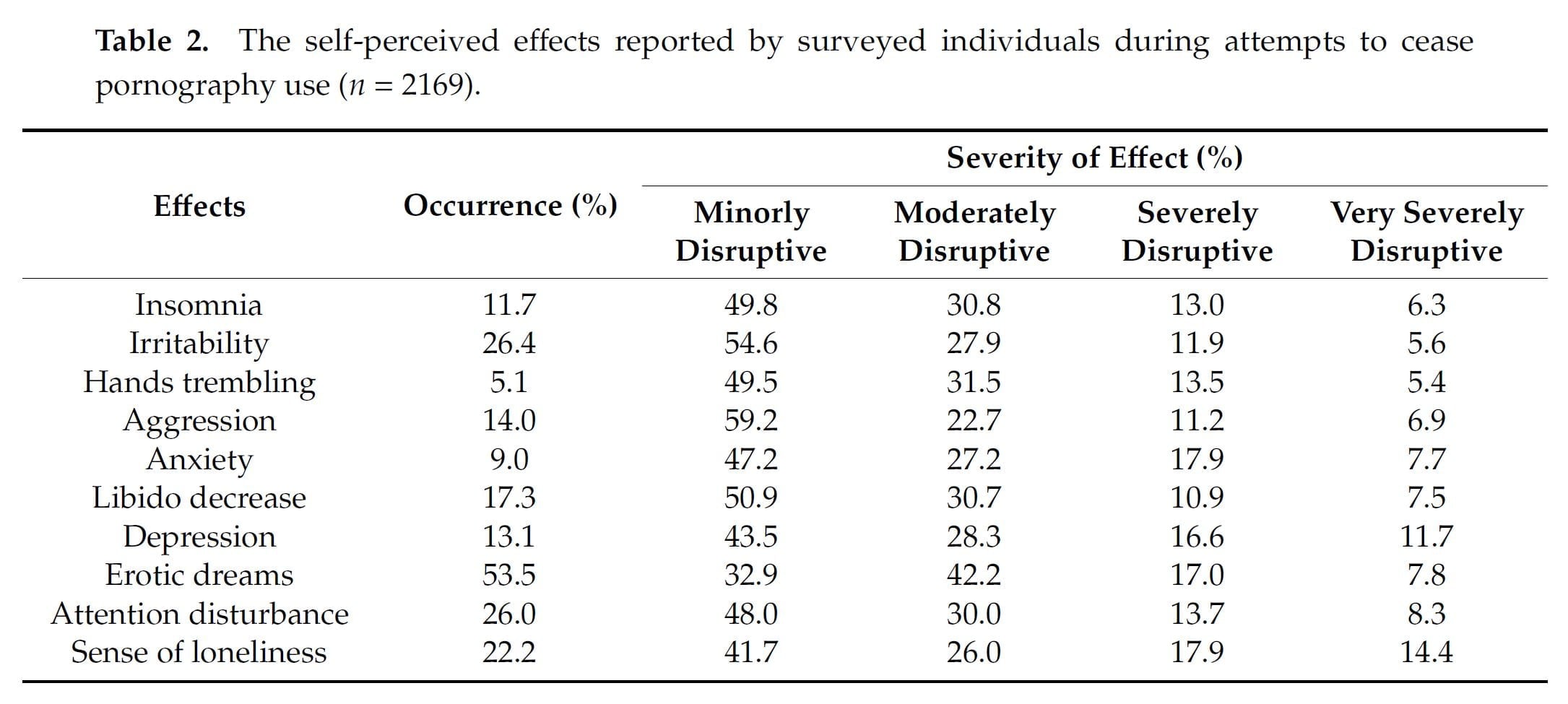

The study reported withdrawal symptoms, even in non-addicts (a definitive sign of addiction-related brain changes):

Among those surveyed who declared themselves to be current pornography consumers (n = 4260), 51.0% admitted to making at least one attempt to give up using it with no dif ference in the frequency of these attempts between males and females. 72.2% of those attempting to quit pornography use indicated the experience of at least one associated e ffect, and the most frequently observed included erotic dreams (53.5%), irritability (26.4%), attention disturbance (26.0%), and sense of loneliness (22.2%) (Table 2).

Debunking the claim that pre-existing conditions are the real issue, not porn use, the study found that personality traits were not related to outcomes:

With some exceptions, none of personality traits, which were self-reported in this study, differentiated the studied parameters of pornography. These findings support the notion that access and exposure to pornography are presently issues too broad to specify any particular psychosocial characteristics of its users. However, an interesting observation was made regarding consumers who reported a need to view increasingly extreme pornographic content. As shown, frequent use of explicit material may potentially be associated with desensitization leading to a need to view more extreme content to reach similar sexual arousal.

STUDY #8: Abstinence or Acceptance? A Case Series of Men’s Experiences With an Intervention Addressing Self-Perceived Problematic Pornography Use (2019) – The paper reports on six cases of men with porn addiction as they underwent a mindfulness-based intervention program (meditation, daily logs and weekly check-ins). All subjects appeared to benefit from meditation. Relevant to this list of studies, 3 described escalation of use (habituation) and one described withdrawal symptoms. (Not below – two more reported porn-induced ED.)

An excerpt from the case reporting withdrawal symptoms:

Perry (22, P_akeh_a):

Perry felt he had no control over his pornography use and that viewing pornography was the only way he could manage and regulate emotions, specifically anger. He reported outbursts at friends and family if he abstained from pornography for too long, which he described as a period of roughly 1 or 2 weeks.

Excerpts from the 3 cases reporting escalation or habituation:

Preston (34, M_aori)

Preston self-identified with SPPPU because he was concerned with the amount of time he spent watching and ruminating on pornography. To him, pornography had escalated beyond a passionate hobby and reached a level where pornography was the center of his life. He reported watching pornography for multiple hours a day, creating and implementing specific viewing rituals for his viewing sessions (e.g., setting up his room, lighting, and chair in a specific and orderly way before viewing, clearing his browser history after viewing, and cleaning up after his viewing in a similar way), and investing significant amounts of time in maintaining his online persona in a prominent online pornography community on PornHub, the world’s largest Internet pornography website…

Patrick (40, P_akeh_a)

Patrick volunteered for the present research because he was concerned with the duration of his pornography viewing sessions, as well as the context in which he viewed. Patrick regularly watched pornography for several hours at a time while leaving his toddler son unattended in the living room to play and/or watch television…

Peter (29, P_akeh_a)

Peter was concerned with the type of pornographic content he was consuming. He was attracted to pornography made to resemble acts of rape. The more real and realistically depicted the scene, the more stimulation he reported experiencing when viewing it. Peter felt his specific tastes in pornography were a violation of the moral and ethical standards he held for himself…

STUDY #9: Signs and symptoms of cybersex addiction in older adults (2019) – In Spanish, except for the abstract. Average age was 65. Contains findings that thoroughly support the addiction model, including 24% reported symptoms of withdrawal when unable to access porn (anxiety, irritability, depression, etc.). From the abstract:

Thus, the aim of this work was double: 1) to analyze the prevalence of older adults at risk of developing or showing a pathological profile of cybersex use and 2) to develop a profile of signs and symptoms that characterize it in this population. 538 participants (77% men) over 60 years of age (M = 65.3) completed a series of online sexual behavior scales. 73.2% said they used the Internet with sexual aim. Among them, 80.4% did it recreationally whereas a 20% showed a risk consumption. Among the main symptoms, the most prevalent were the perception of interference (50% of participants), spending >5 hours a week on the Internet for sexual purposes (50%), recognize that they may be doing it excessively (51%) or presence of symptoms of withdrawal (anxiety, irritability, depression, etc.) (24%). This work highlights the relevance of visualizing online risky sexual activity in a silent group and usually outside any intervention for the promotion of online sexual health.

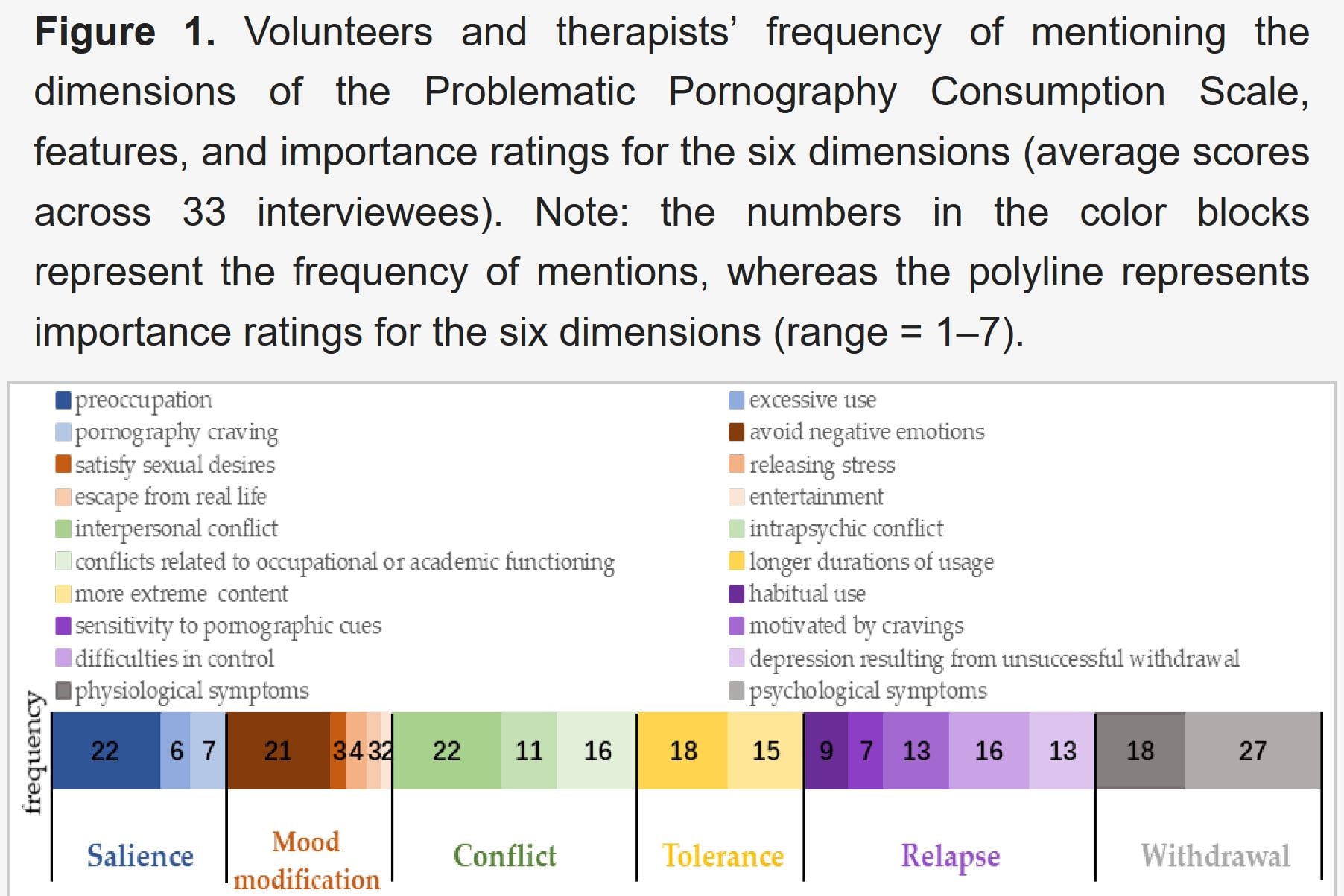

STUDY #10: The Assessment of Problematic Internet Pornography Use: A Comparison of Three Scales with Mixed Methods (2020) – Recent Chinese study comparing the accuracy of 3 popular porn addiction questionnaires. Interviewed 33 porn users and therapists, and assessed 970 subjects. Relevant findings:

- 27 of 33 interviewees mentioned withdrawal symptoms.

- 15 of 33 interviewees mentioned escalation to more extreme content.

Graph of interviewees’ ratings the six dimensions of the porn questionnaire that assessed tolerance and withdrawal (the PPCS):

The most accurate of the 3 questionnaire was the “PPCS” which is modeled after substance addiction questionnaires. Unlike the other 2 questionnaires, and previous porn addiction tests, the PPCS assesses tolerance & withdrawal. An excerpt describing importance of assessing tolerance and withdrawal:

The more robust psychometric properties and higher recognition accuracy of the PPCS may be attributable to the fact that it has been developed in accordance with Griffiths’s six-component structural theory of addiction (i.e., in contrast to the PPUS and s-IAT-sex). The PPCS has a very strong theoretical framework, and it assesses more components of addiction [11]. In particular, tolerance and withdrawal are the important dimensions of problematic IPU that are not assessed by the PPUS and s-IAT-sex;

The interviewees see withdrawal as a common and important feature of problematic porn use:

It also can be inferred from Figure 1 that both volunteers and therapists emphasized the centrality of conflict, relapse and withdrawal in IPU (basing the frequency of mentions); at the same time, they weighted the mood modification, relapse and withdrawal as more important features in the problematic use (basing the important rating).

STUDY #11: Symptoms of Problematic Pornography Use in a Sample of Treatment Considering and Treatment Non-Considering Men: A Network Approach (2020) – Study reports withdrawal and tolerance in porn users. In fact, withdrawal and tolerance were central components of problematic porn use.

A large-scale online sample of 4,253 men ( M age = 38.33 years, SD = 12.40) was used to explore the structure of PPU symptoms in 2 distinct groups: considered treatment group ( n = 509) and not-considered treatment group (n = 3,684).

The global structure of symptoms did not differ significantly between the considered treatment and the not-considered treatment groups. 2 clusters of symptoms were identified in both groups, with the first cluster including salience, mood modification, and pornography use frequency and the second cluster including conflict, withdrawal, relapse, and tolerance. In the networks of both groups, salience, tolerance, withdrawal, and conflict appeared as central symptoms, whereas pornography use frequency was the most peripheral symptom. However, mood modification had a more central place in the considered treatment group’s network and a more peripheral position in the not-considered treatment group’s network.

In the three samples’ networks, withdrawal was the most central node, while tolerance was also a central node in the subclinical individuals’ network. In support of these estimates, withdrawal was characterized by high predictability in all networks (Chinese community men:76.8%, Chinese subclinical men: 68.8%, and Hungarian community men: 64.2%).

Centrality estimates indicated that the subclinical sample’s core symptoms were withdrawal and tolerance, but only the withdrawal domain was a central node in both community samples.

Consistent with previous studies (Gola & Potenza, 2016; Young et al., 2000), worse mental health scores and more compulsive sexual behaviors correlated with higher PPCS scores. These results suggest it may be advisable to consider craving, mental health factors, and compulsive use in screening and diagnosing PPU (Brand, Rumpf et al., 2020).

Additionally, centrality estimates in the six factors of the PPCS-18 displayed withdrawal as the most crucial factor in all three samples. According to the strength, closeness, and betweenness centrality results among subclinical participants, tolerance also contributed importantly, being second only to withdrawal. These findings suggest that withdrawal and tolerance are particularly important in subclinical individuals. Tolerance and withdrawal are considered as physiological criteria relating to addictions (Himmelsbach, 1941). Concepts like tolerance and withdrawal should constitute a crucial part of future research in PPU (de Alarcón et al., 2019; Fernandez & Griffiths, 2019). Griffiths (2005) postulated that tolerance and withdrawal symptoms should be present for any behavior to be considered addictive. Our analyses support the notion that withdrawal and tolerance domains are important clinically for PPU. Consistent with Reid’s view (Reid, 2016), evidence of tolerance and withdrawal in patients with compulsive sexual behaviors may be an important consideration in characterizing dysfunctional sexual behaviors as addictive.

STUDY #13: Three Diagnoses for Problematic Hypersexuality (PH); Which Criteria Predict Help-Seeking Behavior? (2020) – From the conclusion:

Main results of this study show that the “Negative Effects” factor, consisting of six indicators, is most predictive of experiencing the need for help for PH. Of this factor, we specifically want to mention “Withdrawal” (being nervous and restless) and “Loss of pleasure”. The relevance of these indicators in distinguishing PH from other conditions has been assumed [23,28] but has not previously been established by empirical research

Despite the limitations mentioned, we think that this research contributes to the field of PH research and to the exploration of new perspectives on (problematic) hypersexual behavior in society. We stress that our research showed that “Withdrawal” and “Loss of pleasure”, as part of the “Negative Effects” factor, can be important indicators of PH (problematic hypersexuality). On the other hand, “Orgasm frequency”, as part of the “Sexual Desire” factor (for women) or as a covariate (for men), did not show discriminative power to distinguish PH from other conditions. These results suggest that for the experience of problems with hypersexuality, attention should focus more on “Withdrawal”, “Loss of pleasure”, and other “Negative Effects” of hypersexuality, and not so much on sexual frequency or “excessive sexual drive” [60] because it is mainly the “Negative Effects” that are associated with experiencing hypersexuality as problematic.

STUDY #14: The Pornography “Rebooting” Experience: A Qualitative Analysis of Abstinence Journals on an Online Pornography Abstinence Forum (2021) – Excellent paper analyzes more than 100 rebooting experiences and highlights what people are undergoing on recovery forums. Contradicts much of the propaganda about recovery forums (such as the nonsense that they’re all religious, or strict semen-retention extremists, etc.). Paper reports tolerance and withdrawal symptoms in men attempting to quit porn. Relevant excerpts:

One primary self-perceived problem related to pornography use concerns addiction-related symptomatology. These symptoms generally include impaired control, preoccupation, craving, use as a dysfunctional coping mechanism, withdrawal, tolerance, distress about use, functional impairment, and continued use despite negative consequences (e.g., Bőthe et al., 2018; Kor et al., 2014).

Abstaining from pornography was perceived to be difficult largely due to the interaction of situational and environmental factors, and the manifestation of addiction-like phenomena (i.e., withdrawal-like symptoms, craving, and loss of control/relapse) during abstinence (Brand et al., 2019; Fernandez et al., 2020).

Some members reported that they experienced heightened negative affect during abstinence. Some interpreted these negative affective states during abstinence as being part of withdrawal. Negative affective or physical states that were interpreted as being (possible) “withdrawal symptoms” included depression, mood swings, anxiety, “brain fog,” fatigue, headache, insomnia, restlessness, loneliness, frustration, irritability, stress, and decreased motivation. Other members did not automatically attribute negative affect to withdrawal but accounted for other possible causes for the negative feelings, such as negative life events (e.g., “I find myself getting agitated very easily these past three days and I don’t know if it’s work frustration or withdrawal” [046, 30s]). Some members speculated that because they had previously been using pornography to numb negative emotional states, these emotions were being felt more strongly during abstinence (e.g., “Part of me wonders if these emotions are so strong because of the reboot” [032, 28 years]). Notably, those in the 18–29 years age range were more likely to report negative affect during abstinence compared to the other two age groups, and those 40 years and above were less likely to report “withdrawal-like” symptoms during abstinence compared to the other two age groups. Regardless of the source of these negative emotions (i.e., withdrawal, negative life events, or heightened preexisting emotional states), it appeared to be very challenging for members to cope with negative affect during abstinence without resorting to pornography to self-medicate these negative feelings.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!